Tennessee teachers will be restricted from discussing systemic racism with their students — or lose state funding — when legislation approved Wednesday becomes law.

The Senate voted 25-7 for the ban one day after the House easily passed the bill along partisan lines in Tennessee’s GOP-controlled legislature, following several days of fiery debate.

Gov. Bill Lee is expected to sign the bill into law. The Republican governor has not vetoed a bill since taking office.

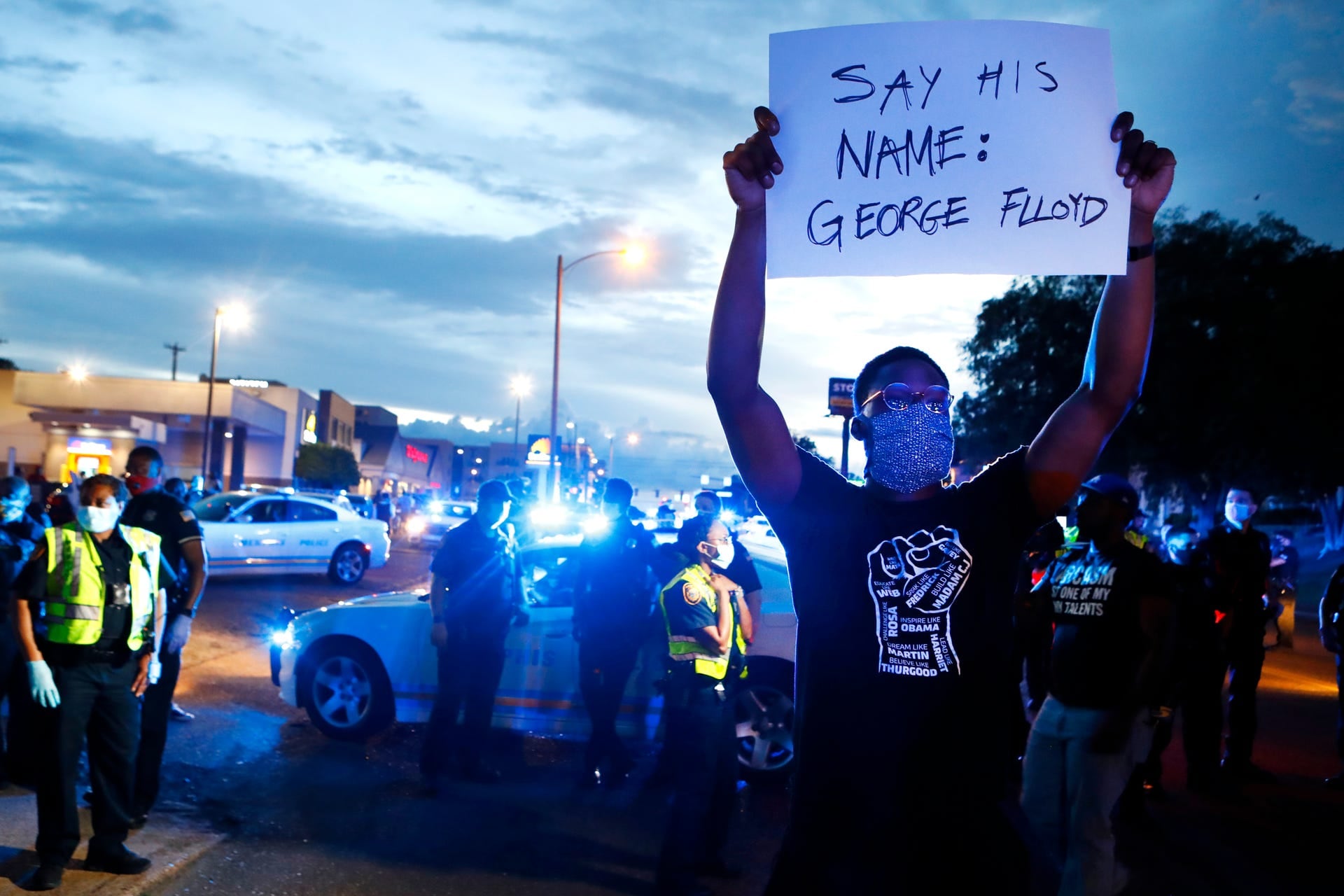

Tennessee becomes the latest state on the verge of limiting the depth of classroom discussions about inequality and concepts such as white privilege as part of a conservative backlash to America’s reckoning over racism.

The legislation allows the state education commissioner to withhold funds from schools and districts where teachers promote certain concepts about racism, sexism, bias, and other social issues that are part of the nation’s history.

Among concepts that teachers will not be able to discuss: that one race bears responsibility for the past actions against another; the United States is fundamentally racist; and a person is inherently privileged or oppressive due to their race.

It’s unclear whether or to what extent those specific concepts are being taught in Tennessee public schools. But white GOP lawmakers were anxious to block lessons they view as divisive, cynical, or misguided. They pushed the prohibitions through the General Assembly during their last three days before recessing for the year.

Republicans were especially disapproving of critical race theory, an academic framework that examines how policies and the law perpetuate systemic racism.

The Senate, which initially rejected the legislation on Tuesday, reversed course after adding several provisions. One new provision will prohibit public schools from including or promoting that “the rule of law does not exist but instead is a series of power relationships and struggles among racial or other groups.”

“That is the very definition of critical race theory,” said Senate Education Committee Chairman Brian Kelsey, a white Republican, calling the ideas “antithetical to everything that we stand for as Americans.”

Scholars define critical race theory as the analysis of how race and the pervasiveness of racism affect individuals and society.

Sen. Katrina Robinson, a Black Democrat from Memphis, called the classroom restrictions “a huge step in the wrong direction” and charged that the bill “breathes more life into racism.”

“How ironic that a body made up of a supermajority of white, privileged men can determine whether even my grandchildren can see reflections of themselves in the history lessons they have in their schools — to even feel a sliver of significance in their existence,” she said on the Senate floor.

Mark Finchum, executive director of the Tennessee Council for the Social Studies, predicted a chilling effect on how educators teach about racism, sexism, and oppression in their social studies, civics, and history classes.

“I think this will cause administrators to put more pressure on teachers, and both administrators and teachers already have enough to worry about without this bill,” he told Chalkbeat.

Finchum also has questions about how the state education department will police classrooms to make sure educators are following the law, as well as how much money districts could get dinged if they don’t.

Republicans’ call for facts-based teaching of Tennessee academic standards came just a few years after lawmakers raised the standards to discourage students from rote memorization of facts. The goal, they said at the time, was to develop critical thinking skills, such as analysis, reflection, and problem-solving.

“Our goal should be to create learning environments that foster dialogue, inclusivity, mutual respect and critical thinking,” said a statement from the Education Trust in Tennessee, which advocates for equity in education and criticized the legislature’s passage of the bill. “Though touted as a strategy to provide clarity and a focus on the standards, this legislation does neither.”

Similar measures have been criticized by other groups, including the Organization of American Historians, the nation’s largest professional organization of scholars of U.S. history.

Speaking to Wednesday’s conference committee as negotiators ironed out differences between the bill’s House and Senate versions, Kelsey singled out The New York Times’ “1619 Project.” The collection of articles and essays argues the nation’s “founding contradictions” emerged in 1619, the year that 20 to 30 enslaved Africans landed in the English colony of Virginia.

“In Tennessee, we believe that the American government began in 1776, we believe that the Constitution is the law of the land, and we believe in the rule of law,” said Kelsey, a Republican from Germantown, near Memphis.

Sen. Brenda Gilmore, a Nashville Democrat and one of two Black legislators on the nine-member negotiating committee, said students need to learn more perspectives — not fewer ones — to understand the complexities and nuances of U.S. history.

“It will be harmful,” said Gilmore, who presented a minority report opposing the proposal.

“What we have to do is acknowledge that slavery existed, that today there’s still racism,” she said. “But there’s no way to sweep this under the rug and pretend that it did not happen or to gloss over it.”