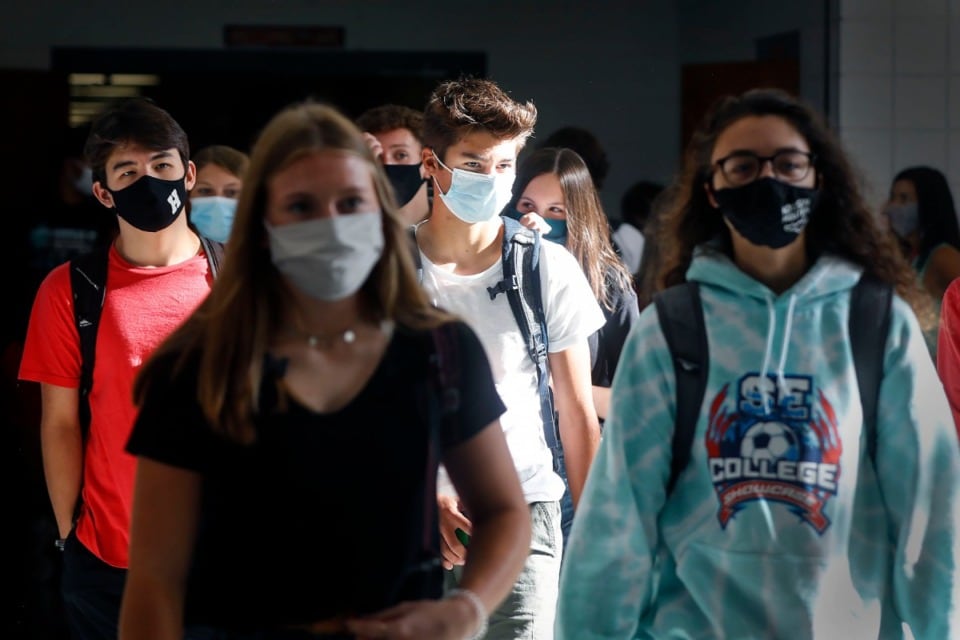

Children ages 18 and under account for more than 12% of COVID-19 cases so far across Tennessee, with high school-age students making up almost half of that number, according to data released Tuesday by the state Department of Health.

The information, which includes county-by-county and racial breakdowns of the cases, was released in response to public calls for statewide data to help families determine whether it’s safe to send their students back to school in person.

The latest research has concluded that children can transmit the highly contagious virus, even if they don’t show symptoms, with those between the ages of 10 and 19 spreading it at least as well as adults do.

But Gov. Bill Lee said Tennessee will not report the number of confirmed student cases linked to schools, or share information about teachers and staff who test positive for the coronavirus — lessening parents’ ability to fully understand possible exposure to the respiratory illness in their children’s school buildings.

Dr. Lisa Piercey, state health commissioner, said her department can’t be more specific due to federal privacy laws aimed at protecting sensitive health information of patients, as well as student records. News reports indicate more than 150 cases have been confirmed among students and staff since Tennessee schools began reopening in late July.

“We have seen many school districts voluntarily give that information,” Piercey said. “If those school districts, in consultation with their board attorneys, feel like that’s appropriate, then they have the right to do that.”

The discussion came during a press conference where the governor and several cabinet members faced some of their toughest questions yet about their handling of the pandemic, especially as it affects schoolchildren, teachers, and their families. A second press conference on the virus is scheduled for Thursday.

The officials waded into controversial decisions by some local education leaders in response to staffing shortages caused by the coronavirus as most schools continue to reopen for in-person instruction.

Lee said it’s up to local officials if they want to designate teachers as “critical infrastructure workers” under federal guidelines, as at least six Tennessee school districts have done. The designation has the effect of skirting public health guidance from state and local officials and requiring employees who are potentially exposed to coronavirus to report to work instead of isolating at home.

“The decision is the district’s,” said the governor, who has urged school leaders to reopen their classrooms and provide in-person instruction whenever possible. “If they choose that policy on their own, we’re giving them guidance.”

Earlier Tuesday, Piercey and Education Commissioner Penny Schwinn reminded school leaders that employees who have tested positive for COVID-19 must isolate for 10 days before returning to work, and also must be symptom-free for at least 24 hours.

In a joint letter to superintendents, they made it clear that any decision to deem educators as essential workers to keep them on the job — potentially unsafely — is not aligned with medical guidance.

“While isolation and quarantine due to COVID-19 will have a disruptive effect on school operations, such protocols are advised by state and federal public health officials in order to protect the community and mitigate further virus transmission,” the commissioners wrote, urging superintendents first to seek legal counsel on the matter.

Lee also said Schwinn and the Department of Education are “making major adjustments” to a massive new plan for school districts to conduct “wellbeing checks” on every child in the state during the pandemic.

Created by Schwinn’s staff as part of her Child Wellbeing Task Force, the plan was released this month but quickly drew pushback from lawmakers concerned about government overreach. Last Friday, Schwinn wrote them that the program, while well-intentioned, “missed the mark.”

“We have scaled it back, pulled it back, and [are] doing a reset on it,” the governor added on Tuesday. He said the department’s focus will be to safely reopen schools and ensure that students receive a high-quality education.

Tensions between student privacy and public health transparency is at the heart of the latest reversal by Lee’s administration on sharing data related to COVID-19 cases.

In July, state officials said the state would not compile case data by school, even as the governor promised to make data-driven decisions on school safety. After public outcry over that call, he reversed course and promised that information was on the way.

But the governor and his health commissioner, citing privacy concerns, said Tuesday that the state will stop short of releasing data on student or adult transmission in schools.

“The real challenge is to provide as much information as possible to provide for transparency and to give information that’s important to the public — but to continue to adhere to privacy restrictions” under federal law, Lee said. “That’s a balance.”

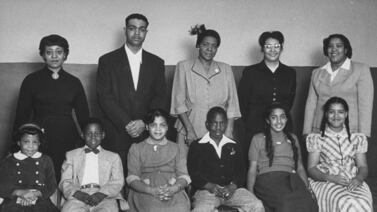

Data released on Tuesday is broken down by gender, race, and ethnicity. It shows that white children make up almost 45% of the cases among youngsters 18 and under, Hispanic children 25%, and Black children almost 18%.

A separate data set, which will be updated weekly, shows COVID-19 cases among school-age children from 5 to 18.