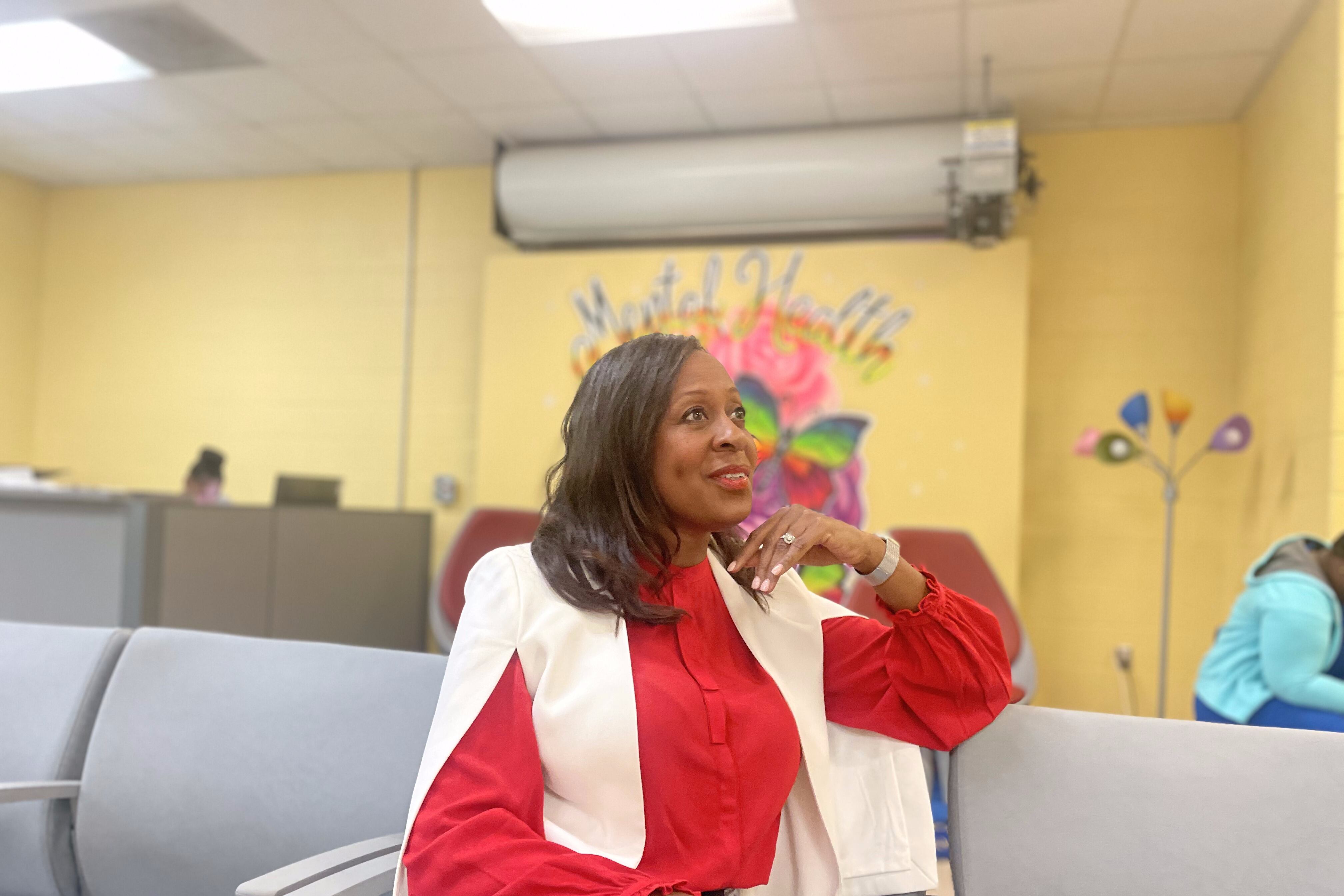

Michelle McKissack, former chair of the Memphis-Shelby County Schools board, has a special place in her heart for the students of Hope Academy. But she wishes they never arrived there in the first place.

The school, housed on the second floor of the Shelby County Juvenile Detention Center, serves children who are in the custody of the criminal-justice system, with a goal of keeping them current with their studies and facilitating their return to school when they’re released.

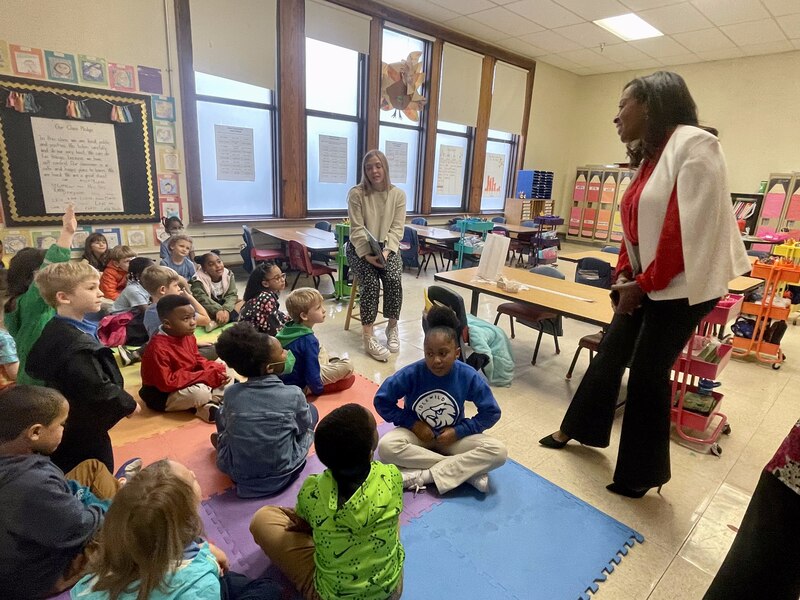

During a visit to the school last month, as students received lessons in algebra, literacy, and current events, McKissack said she couldn’t help thinking about how things could’ve turned out differently for those students.

What if they’d had more support from the surrounding community? What if the city was more engaged as a partner with the school system in improving pre-kindergarten education, increasing access to internships, and bolstering after-school and summer programming so that children have constructive, safe things to do outside the classroom?

“There’s a lot of talk about juveniles in our city and how they’re wreaking havoc, but we have to invest in them,” McKissack said. “This is an illustration that we’ve got to start this way early.”

It’s that thinking that has McKissack, who joined the board in 2018 and won reelection to her District 1 seat in August, considering a run for mayor of Memphis. She formed an exploratory committee in September for a campaign to succeed Jim Strickland, whose term expires at year end, and she plans to formally announce her decision by the end of the month.

Over four years, McKissack said, she has come to grips with the school board’s limited ability to make real, communitywide change on its own. Her tenure as board member and chair has seen Tennessee’s largest school district publicly clash with the city and county governments over school funding and responsibility for broader regional issues that plague the schools, such as juvenile crime and rising gun violence.

But with two of her former board colleagues, Miska Clay Bibbs and Shante Avant, now on the Shelby County Commission, McKissack said it would be a breakthrough to also have a city leader who understands the school system and what children need.

“You would be gaining a really huge advocate at the city level,” said McKissack, part of a growing field of mayoral candidates that includes a businessman, the county sheriff, and a former judge and TV star. “We have to think bigger. We have to believe bigger, and I’m forever the optimist who wants to work toward solutions.”

McKissack led the board through district turmoil

McKissack, a native Memphian and former broadcast journalist, got involved in schools believing in the power of individuals to make a difference from the inside.

As her four children passed through their neighborhood school, Downtown Elementary, McKissack became a parent leader — at one point serving as parent-teacher association president — who helped establish the annual Turkey Trot and Heart 4 Art fundraisers.

“I was a hardcore volunteer,” McKissack recalled in December. “I mean, you would have thought I was on payroll. I was there constantly, fundraising, doing this and that.”

That work led McKissack to serve as a founding board member for Crosstown High School, a charter school that opened in 2018. She also served on several state parent advisory councils.

McKissack recalled that her sister was the first person to ask her if she’d ever considered running for school board. Initially, she rejected the idea. But as more people asked her the same question, she eventually was convinced, and she won election in 2018.

Her term as chairperson began in September 2021, amid the tortuous recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic, and culminated with the resignation of Superintendent Joris Ray under a cloud of scandal.

Ray left with a $480,000 severance package, and under McKissack’s leadership, the board called off an outside investigation into whether he violated district policies about romantic relationships with subordinates, without releasing any findings.

What was supposed to be a comeback year turned into another year marred by the pandemic as MSCS’ over 100,000 students and 6,000 teachers weathered two COVID waves and growing community frustration over poor academic performance. A shooting inside Cummings K-8 School and overall escalating gun violence in Memphis rattled the district and city as a whole.

“It was an intense year, that’s for sure,” McKissack said.

“But what that taught me is that life is going to throw you curveballs, leadership is going to throw you curveballs, and you have to just figure out how you’re going to deal with it and move forward,” she said.

Violent incidents served as a call to action

In September 2022, as McKissack’s term as chair was ending, Memphis made national headlines for some high-profile incidents of violence — first the kidnapping and killing of Eliza Fletcher, a Memphis pre-kindergarten teacher and mother of two, and then, days later, a shooting spree across Memphis that left four people dead and three others wounded.

Just days earlier, McKissack was among the MSCS officials who hit back at Strickland over his comments linking declining school enrollment to juvenile crime and criticizing the district over its role in enforcement of truancy laws. McKissack called for a comprehensive approach to crime and violence in Memphis and suggested that local elected officials convene an emergency summit to explore solutions together.

“It’s not just the one problem of getting guns off the streets or tackling truancy — it’s all of it,” McKissack said at the time. “We’re operating too much in silos.”

The incidents, and the response, served as a call to action for McKissack. She said she now sees herself as the kind of leader who could get the district and local government to work together to strengthen the schools and opportunities for students.

For instance, she believes the city should play a bigger role in boosting job training through the school system — especially given Ford Motor Co. and SK Innovation’s joint venture to build an electric vehicle battery plant in nearby Haywood County.

She pointed to Manassas High School in her district as an example of the kind of workforce training she’d like to see across the city. The North Memphis school boasts a dual enrollment welding program in collaboration with William R. Moore College of Technology.

Getting workforce training while still in high school could have an especially large impact on students from low-income families who may not have the resources for a traditional college degree. Nearly 80% of Manassas’ over 300 students come from economically disadvantaged families, according to state data.

“I didn’t know that this was happening here in our city, and we need more of that for our students,” McKissack said. “This can help them out of poverty. We’ve got to get away from the emphasis on going to a traditional four-year college.”

City, county pressed to invest more in schools

McKissack wants local governments to help more with direct funding as well.

Since Memphis City Schools merged with Shelby County Schools a decade ago, the city currently contributes only about $1 million to MSCS annually — less than 1% of the district’s total funding.

The current MSCS board chair, Althea Greene, said she often fields questions from constituents about why the city doesn’t invest more money, given its broader stake in the performance of the school system.

“I often don’t have a good answer for them,” Greene said. “The next mayor of Memphis should have an interest in Memphis-Shelby County Schools. We don’t get the level of support that we should get from them.”

Under the merger arrangement, the Shelby County Commission is the district’s principal local funding authority, but relations between the two bodies have been tense. MSCS has long sought additional funding from the Shelby County Commission to address hundreds of millions of dollars of deferred maintenance at its many aging school buildings.

Shelby County commissioners recently agreed to contribute $77.5 million for a new high school in the Cordova area, as part of an agreement for MSCS to cede control of Germantown High School to the suburban Germantown district in accordance with a new state law.

But for the past two years, the county commission has granted the district less than half of its $55 million requests for capital improvement funds for other projects throughout the district. Some on the commission urged district officials to start building a case for raising taxes countywide or suggested they turn to the city government instead.

McKissack pointed to Idlewild Elementary in her district as an example of what’s possible if city and county leaders committed more money to improving schools.

Located in Midtown Memphis’ historic Central Gardens neighborhood, the school received the highest state rating for math and English-language arts on the Tennessee Department of Education’s latest report card. The school serves nearly 500 students, nearly 60% of whom are children of color and about 30% of whom come from low-income families.

“It’s academically at the very top of schools in our district, it’s wonderfully diverse, and it’s just what we aspire to be as a district,” she said. “It’s not this brand new, beautiful building, but a lot of great things are happening there.”

McKissack lauded Idlewild’s community garden and green space, which are the result of donations and collaborations between the school and community partners.

As a mayoral candidate, McKissack said, she’d advocate for more such public-private partnerships, with the city and county pitching in.

“If we can provide tax incentives to companies and provide them with funds,” she said, “why can’t we do the same thing for our schools?”

Samantha West is a reporter for Chalkbeat Tennessee, where she covers K-12 education in Memphis.