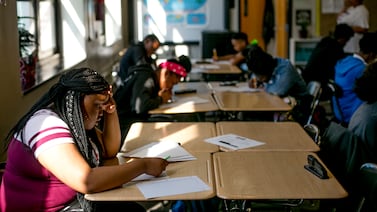

State legislation limiting how teachers can discuss topics like institutional racism and white privilege has thrown a damper on critical conversations in classrooms across Tennessee, students and educators say. They shared that feedback as part of Thursday’s panel hosted by Chalkbeat Tennessee and the Education Trust of Tennessee on how laws targeting critical race theory and controversial books are affecting Tennessee students and teachers.

The impacts of the law aren’t purely academic. Students from Memphis, Nashville, and Knoxville said they’re disheartened by the law and its fallout, at a time when leading health officials are warning of an accelerating youth mental health crisis brought on by the pandemic.

A Centers for Disease Control and Prevention survey released Thursday revealed more than four in 10 teens report feeling “persistently sad or hopeless,” and one in five say they have contemplated suicide, evidence of spiking mental health concerns among teens over the last decade.

Angelie Quimbo, a senior at Hillwood High School in Nashville, said she and other students of color are saddened by the law.

“The nature of the bill was to remove this sort of restriction and bias from the school system,” she said, “but instead I feel like it’s actually adding more restriction and bias, and kind of limiting the access of how students get information that they need that’s actually impacting them.”

Quimbo was among a panel of students, educators, and experts at Thursday’s virtual panel.

Like Quimbo, Ivy Enyenihi, a junior at Farragut High School in Knoxville, called the law disheartening, adding that after she visited the state capitol during a “day on the hill” event, it was hurtful to return to her community and know that “nobody’s paying attention to what’s going on there, there’s no conversation about it, people aren’t even aware.”

And Jamal Wright, a senior at Bluff City High School in Memphis, says his education doesn’t reflect the reality of what he sees on the news.

Teachers, too, are facing heightened stress, the group told panel moderator and Chalkbeat Tennessee bureau chief Cathryn Stout. Tennessee is among eight states that have passed widely varying laws restricting how schools teach about racism and sexism over the last year, amid national fury from conservatives opposing critical race theory, an academic framework that studies how policies and laws perpetuate systemic racism.

The Volunteer State’s law, enacted last spring, restricts teachers from discussing 14 concepts the legislature deemed divisive, including that the United States is fundamentally or irredeemably sexist or racist and that a person is inherently privileged, racist, sexist, or oppressive because of race or gender.

In November, Education Commissioner Penny Schwinn signed off on emergency rules for regulating the law. Districts found to be violating the law could face financial penalties, and the State Board of Education could suspend or revoke teachers’ licenses if their district fires them for a violation.

Many teachers in states with new laws targeting how race and gender are taught say they haven’t changed their approach and there is little evidence that it’s led to sweeping curriculum changes. Still, they say the ambiguity of the laws, plus greater scrutiny from parents and administrators, are chipping away at discussions of racism and inequality.

How that looks varies from school to school, classroom to classroom, and educator to educator, said Diarese George, founder and executive director of the Tennessee Educators of Color Alliance, a nonprofit, nonpartisan organization aimed at amplifying the voices and perspectives of teachers of color.

In areas where people are engaged with the topic, George said he’s heard some teachers are “finding ways to be resistant.” Others, he said, “are not touching this at all” and cut conversations short because they’re fearful of losing their job, or worse, losing their license.

“Folks are literally picking and choosing their battles,” George said.

Ann Varnedoe, who teaches ELL and world history at Hillwood High School in Nashville, hasn’t changed her approach. Varnedoe said she’s lucky that her school’s administrators have remained supportive of her teaching decisions and students’ identities.

Still, Varnedoe said the law has hurt some students. Although Hillwood administrators never took down Black Lives Matter posters after the law passed, Varnedoe recalled a day when a Black student came to her, clearly distraught, and said “Miss V, we can’t talk about Black Lives Matter anymore.”

“He was so disappointed, he was so engaged, it’s relevant to his life, it’s something he’ll take with him as he moves on from school,” Varnedoe said. “Robbing them of an opportunity to talk about their identity, to talk about the world around them, is such an injustice to me.”

That’s why, Varnedoe said, “I’ve stuck to what I know, which is to teach history in a way that is true and to stand with our students and their identities and to say to them: You’re safe here. You’re safe to explore these things that are difficult and these things that affect you and your families.”

Karen Streeter, a licensed educational psychologist in Memphis, said she was struck by the overwhelmingly negative emotions expressed by both students and teachers. While jotting down all the emotional words used by panelists, she noticed “none of them were positive.”

“I heard frustrated, isolated, uncomfortable, disheartened, hurt, sad, confused, awkward, anxious, ill-equipped, disappointed, stressed, and confused,” Streeter said. “That’s a lot of negative energy, a lot of negative emotions on both the sides of the students and the teachers, and that’s a lot to have to deal with when you’re also trying to teach every day and learn every day.”

To combat this, Streeter suggested teachers and administrators monitor for what she called “the desolate Ds” — disruptive behavior, disengagement, dreaminess, depression, and “danger watching,” or heightened anxiety. And teachers notice any of these changes in an adult or student, they should be clear they’re open to communication, listen, and provide resources, Streeter said.

In encouraging teachers to learn as much as they can about the law, George highlighted resources from the Education Trust of Tennessee and the ACLU of Tennessee.

Despite all the challenges, Quimbo and Enyenihi trust their teachers to deliver instruction in a fair and balanced manner, even as they grapple with heightened scrutiny and restriction.

Quimbo, who has noticed some of her teachers in her Advanced Placement classes have been “cognizant and weary” of how they talk about race, said she trusts her teachers to encourage healthy discussion despite their own personal bias or the bias she says is part of any history textbook.

“People have their own opinions. If something slips out with their personal opinions, that’s completely fine as long as we explore the possibilities of other opinions as well,” Quimbo said. “Just having a full spectrum of open discussion is something I really value in the classroom, which is why I really value the consideration of my teachers and their delivery of lessons.”

Samantha West is a reporter for Chalkbeat Tennessee, where she covers K-12 education in Memphis. Connect with Samantha at swest@chalkbeat.org.