Tennessee’s textbook commission moved Friday toward approving broad guidance for school districts to avoid having their books banned statewide under a new library law, even as one member sought to dig into the details of how to define what is age-appropriate for students.

Commissioner Laurie Cardoza-Moore, a conservative activist, lashed out at the award-winning young-adult novel “Hatchet” as an example of one book that should be pulled under a 2022 law that aims to ensure library materials are “appropriate for the age and maturity levels” of students who may access them.

“I’m here to represent parents,” said Cardoza-Moore, who lives in suburban Williamson County, south of Nashville, where “Hatchet” was one of 31 texts challenged last year under new English language arts curriculum.

“The content is not only too mature or inappropriate, but it is vulgar,” she said about the 1986 Newbery Award-winning wilderness survival novel. “Does this bring out the best for our students, our children?”

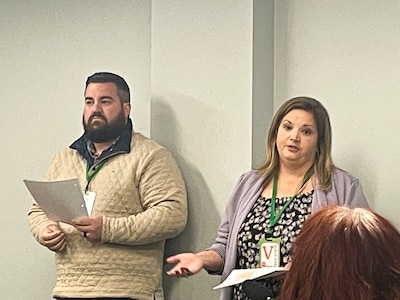

But Linda Cash, who chairs the Tennessee Textbook and Instructional Materials Quality Commission, said the new law directs the appointed 11-member panel to provide guidance — not to set strict rules or regulations.

It’s also not the commission’s job, Cash said, to define what constitutes violence, sexual content, vulgar language, or substance abuse for educators and school officials who already are supposed to be screening library books and other teaching materials for age-appropriateness.

The law — one of a spate of school censorship measures passed by the GOP-controlled legislature and signed by Republican Gov. Bill Lee since 2021 — has elevated tensions over what can be taught about race, sexuality, and history in Tennessee public schools, including the extent to which books and curriculum should reflect the diversity of America’s people and ideas.

Across the nation, classrooms have become a battlefront for conservatives wanting more “patriotic” education and less instruction that touches on systemic racism, racial bias, sexuality, and gender identity.

Tennessee’s laws and book bans spark challenges

Tennessee was among the first few states to enact a law intended to restrict K-12 classroom discussions labeled as critical race theory about the legacy of slavery, racism, and white privilege. That field of study, typically found at the college level, explores how policies and the law perpetuate racist systems.

This year, as book challenges and bans increased, lawmakers passed the governor’s plan requiring periodic library reviews “so parents are empowered to make sure content is age-appropriate.” A second measure gives the state textbook commission veto power over local school board decisions on book challenges.

Currently, several school boards are dealing with challenges and at least one lawsuit.

This week, the school board in Sumner County, north of Nashville, voted 7-3 to keep the children’s book “A Place Inside of Me” on shelves following one parent’s complaint. The book includes a poem and illustrations showing a Black child dealing with his emotions after a police shooting.

And during a court hearing last week in Williamson County, a judge hinted that he’ll likely dismiss a lawsuit filed by a conservative parents group over curriculum that the group claims violates Tennessee’s law prohibiting the teaching of critical race theory.

The newest law directs the textbook commission to provide guidance on age-appropriateness to districts by early December. The commission is examining model guidance from the Tennessee School Boards Association, as well as recommendations from a school librarian advisory panel, as it works with the education department to issue the new guidelines.

The law also gives the commission — which comprises teachers, administrators, and citizens — the authority to ban books statewide in response to appeals of local school board decisions about challenged materials.

In addition, the statute directs the commission to develop an appeals process, which Cash said the panel will work on in January.

But Cash, who is superintendent of Bradley County Schools, hopes there will be no need for appeals.

“I really trust and believe in our local districts to manage this process, and I think they will,” Cash told Chalkbeat.

Librarians defend their credentials to select books

Two school librarians who spoke before the commission on Friday said it’s “very rare” for schools to receive complaints about library books.

Katie Capshaw, president of the Tennessee Association of School Librarians, said she’s received only two complaints in nine years as a librarian. Both matters were worked out in discussions with parents, she added.

Blake Hopper, a school librarian in rural Claiborne County, said he’s fielded no complaints in nine years on the job.

Both librarians served on the commission’s advisory council to develop the new guidance. Their primary message to commissioners: Schools serve a diverse student population and need local flexibility to help their students become lifelong readers.

What might seem inappropriate for one student’s age and maturity level may not apply to another student in another city or town, they said, urging the commission not to issue blanket statewide bans.

“Our job as librarians is to get what’s best for our students,” Capshaw said.

They took issue when Cardoza-Moore said she’s heard reports that some school personnel don’t have time to properly screen books “dropped off” at their doorsteps.

“Books are not dropped off at a school,” Capshaw responded. “The way that it works is that books are chosen, which is why there’s a selection policy.”

She said librarians are trained to choose books and usually are given a budget to purchase them, or must raise the money through fundraisers.

Commissioners identified details that they want to eventually include in their guidance, such as how long the review process should last and how many times the same book can be challenged.

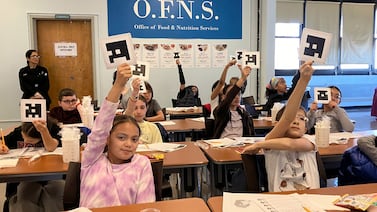

Meanwhile, 19 education advocacy and community organizations have banded together to form the Tennessee Coalition for Truth in Classrooms to oppose censorship of instruction and materials and “promote the teaching of truthful history in our schools.”

“The development of false narratives and attacks on diversity and equity and inclusion efforts are causing disruptions in our schools, hindering our students’ learning, and negatively impacting teachers’ mental, social, and emotional well-being, as they’re being threatened with a range of action,” said Gini Pupo-Walker, state director of the Education Trust in Tennessee, which spearheaded the coalition.

You can watch the full commission meeting here.

Marta W. Aldrich is a senior correspondent and covers the statehouse for Chalkbeat Tennessee. Contact her at maldrich@chalkbeat.org.