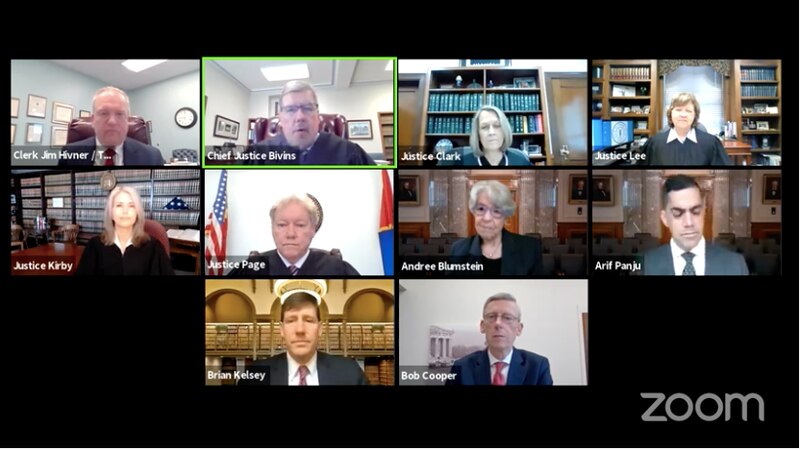

Attorneys for and against Tennessee’s overturned school voucher law went before the state’s highest court Thursday to argue whether state lawmakers have authority to create a major education program that applies to only two counties without local approval.

The Tennessee Supreme Court heard more than an hour of oral arguments on the state’s effort to restore a 2019 law championed by Gov. Bill Lee. The law would give taxpayer money to eligible families in Memphis and Nashville to pay toward private school tuition and other private education expenses.

The five-justice panel is expected to rule in the next few months on what Chief Justice Jeff Bivins called “a very difficult and a very important case.”

Hanging in the balance is Lee’s quest to create an education savings account, or ESA program. The initiative was to start last fall with 5,000 students and cap at 15,000 students in the fifth year, with the state reimbursing districts for any lost funding during the first three years.

Lee called the program key to giving parents more education choices for their children. But the GOP-controlled legislature was only able to pass it by assuring some Republican lawmakers that their own schools would be shielded from its application, leaving only the state’s two largest counties singled out.

A lower court overturned the law a year ago, just months before the controversial program was to launch and begin absorbing students from Shelby County Schools, Metropolitan Nashville Public Schools, and the state-run Achievement School District. Last fall, the Tennessee Court of Appeals unanimously upheld the ruling.

“At its core, this case is about enhancing educational opportunity for low-income children in Tennessee’s lowest-performing schools,” said Andree Blumstein in her introduction to the state’s case on behalf of the state attorney general’s office. “It’s about offering those children the same chance and equal opportunity that more privileged students have to pursue an education that best meets their particular needs. And the ESA pilot program is intended as a first step in that direction.”

A lawsuit filed by Metropolitan Nashville and Shelby County did not address the merits of school choice but instead challenged the law as a violation of Tennessee’s so-called “home rule” provision. In 1953, a state constitutional convention added the provision to restrain legislative power over local governments.

Attorneys for Metro Nashville and Shelby County say the voucher plan would impose a financial burden by affecting state and local funding for public schools without giving local officials or voters a say. Their governing bodies were on record opposing the governor’s plan.

“It is a local bill that applies only to two counties and it applies to them in their governmental capacities by subjecting them to a unique school funding formula,” argued Nashville law Director Bob Cooper on behalf of the two counties.

In its latest appeal, the state argues that home rule does not apply in this case because the program is considered a pilot initiative that the legislature potentially could expand to other areas of the state. The state also contends the plaintiffs don’t have standing because the case applies to school districts, not the county governments, and that the law would not affect any county in its governmental capacity.

Justices aggressively questioned attorneys on both sides of the voucher case, especially about the funding mechanism that eventually would siphon off millions of dollars from local school systems.

Tennessee’s funding formula for public schools is enrollment-driven and, in addition to requiring allocations from the state, stipulates that local taxpayers also contribute thousands of dollars toward each student’s education costs. But Cooper argued that the way the law was written, the local cost for education could not be reduced, even if voucher students left for private schools.

“Your honor, this ESA Act is like the Hotel California. Students check out of the school district, but financially they never leave,” he said, paraphrasing lyrics in a 1977 hit by the Eagles band.

Arguing for the state, Blumstein said any potential financial harm is speculative. “If there is substantial financial harm, they would have standing when that harm occurs,” she said.

Sen. Brian Kelsey, arguing as an attorney for the pro-voucher Liberty Justice Center in Chicago and an intervenor in the case, said local funding for schools would be unaffected by the transition.

“Their only real beef with the statute is the policy decision of where these children are educated and whether or not they go to private schools,” said Kelsey, a Germantown Republican who chairs the Senate Education Committee.

Legislative staff estimated the cost to the state would be $37 million during the program’s first year, growing to $111 million in the fifth year and beyond.

More than 10 parties submitted their own briefs in this case, including the anti-voucher Tennessee NAACP and pro-voucher Alliance for School Choice. A dozen current and former Republican legislators who sponsored or co-sponsored the voucher legislation also filed a collective brief seeking clarity around interpreting and applying the Constitution’s home rule provision.