When the COVID-19 pandemic hit last March, I did what teachers everywhere did: I scrambled.

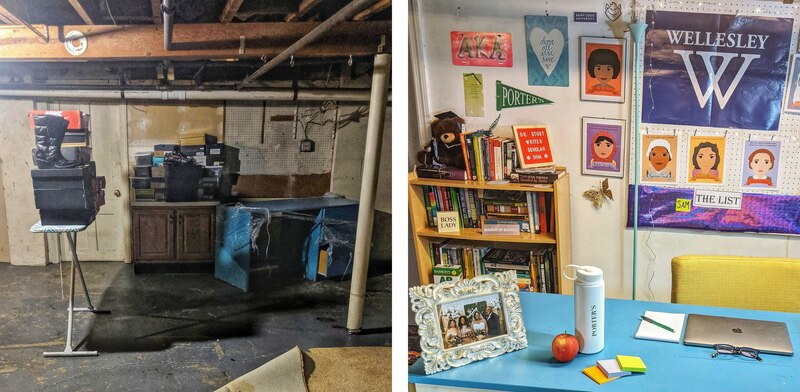

I Googled distance learning, virtual learning, and asynchronous learning. I plugged into a digital village of educators in Facebook groups where we swapped lesson plans and fears. And I studied the educational series Crash Course, trying to tap into my inner John Green, even though my transformed basement studio was laughable compared to the author and YouTuber’s professional studio. When the pandemic hit, I scrambled, and then, with the help of my village, I shifted.

I was in a well-resourced private school in Connecticut, with creative educators and a supportive head of school, and even still, teaching in a pandemic was frightening and foreign territory. Countless conversations with friends and fellow teachers in Shelby County Schools and other districts confirmed that the conditions in their public schools were doubly difficult, due to unstable internet connections, missing students, and endless other issues that stretched teachers’ bandwidth and hearts as they worked to reconnect the disconnected. I also knew that at such a time as this, I needed to strengthen my connection with the people and issues that matter most.

I knew I needed to come home.

For the last five years, I have flown regularly between Hartford, Connecticut, and Memphis, dedicating my summers and school breaks to my Whitehaven stomping ground and my hometown, but when the pandemic left me and millions of others grounded, I knew where I was called to be. I was humbled when Chalkbeat offered me the opportunity to serve as its Tennessee bureau chief, because my life’s work aligns with Chalkbeat’s mission of education equity.

For three generations, my family has worked in all levels of education, from the classroom to the school board. I began following the family path with my first job as a health educator with Girls, Inc. during my teenage years at Central High School. Later, I worked as a community editor and reporter at The Commercial Appeal, where I mentored aspiring journalists. I also taught college students while earning a doctorate, and most recently, I served as a teacher, history department chair, and assistant dean of equity and inclusion at Connecticut boarding schools. I saw inequality magnified, and I challenged my students to use their connections and resources not just for charity, but also for structural change.

I taught remarkable students with a wide range of talents, privileges, and challenges. Like teenagers everywhere, many of my students struggled with relationship drama, mental health issues, and learning disabilities. Many had good family support, but for those who didn’t — those with whom I often worked the most closely — the game changer was having a well-resourced school that provided the services they needed.

On campus, they could get unlimited tutoring, weekly therapy, daily health care, judgment-free contraceptives, free toiletries, three meals a day, fitness classes, evening homework help, and, importantly, a safe place to sleep. This model has been replicated for public school students by the SEED Foundation of Washington, D.C.

In the Bluff City, school, city, and county leaders have to work together to create urban villages that support and protect our students if we want to catapult our reading levels, ACT scores, and juvenile crime rates from near the worst in the state to the best in the nation. You can’t have strong schools in a broken village, and too many of our villages are suffering in this place that we once called “the city of good abode.”

Memphis journalists have always been on the front lines of reform, from the anti-lynching activism of publisher Ida B. Wells-Barnett to the thought-provoking columns of writer and disc jockey Nat D. Williams. When we do our jobs well, journalists get beneath the spin and explain which initiatives work and which projects waste money, deliver poor results, or harm the public. We highlight the discrimination and the diversity double-talk that abounds. And we allow our pages and websites to serve as platforms for the changemakers in our community.

I invite Chalkbeat Tennessee readers to tell us about the tensions, trends, turning points, and trailblazers that are influencing public education in your community. Our email is open to your tips, story ideas, and event announcements, and our pages are open for you to contribute First Person and How I Teach columns. You can type, record, or dictate your thoughts, because writing levels should never be barriers to agency.

I look forward to working with all who are willing to dismantle the barricades to knowledge and education equity wherever they stand, so that we may make stronger schools and safer neighborhoods for Shelby County students from Voodoo Village to Parkway Village and every village in between.