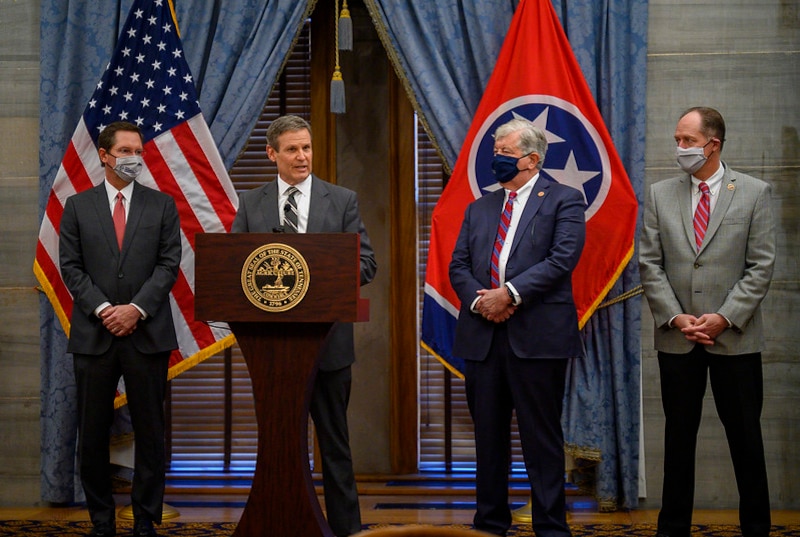

In the pitched debate over school reopening, Tennessee Gov. Bill Lee has repeatedly chided leaders of the state’s two largest school districts for not “putting the needs of students first.” His Republican colleagues in the state legislature are threatening to strip funding from the Memphis and Nashville districts if they don’t pivot quickly and reopen their classrooms.

Although Nashville announced a gradual return starting this week, Shelby County Schools Superintendent Joris Ray has stood firm. The district is sticking with all-remote learning indefinitely. Ray accused state leaders of being out of touch with the needs of Memphis students, who are mostly Black, living in poverty, and disproportionately affected by the deadly virus.

The profound disconnect is the latest example of how a decade-long rift between Tennessee’s state-level decision-makers and urban school leaders can boil over and shape policy affecting the state’s most vulnerable students. Like previous state battles involving Memphis and Nashville, this one is shaped by politics, race, and power — with both sides claiming the moral high ground.

“We’ve seen this before,” Memphis City Councilman Martavius Jones said of the seemingly intractable debate. “It feels like another case of us versus them.”

New, however, is the global health crisis that is disrupting classrooms and disproportionately affecting people of color. The stakes are high because COVID-19 is a life-threatening virus that is putting a generation of students at risk academically and emotionally.

“At the end of the day, our children are suffering,” said Dianechia Fields, a Memphis parent who wants state and local leaders to find a way to collaborate. “At some point, we have to stop fighting each other and sit down and come to reasonable and sensible solutions.”

The reddening of Tennessee

Much of the fracture can be traced to politics.

Mirroring a regional flip, Republicans gained control of Tennessee’s legislature in 2008 and, two years later, the governor’s seat, too. That historic shift, in a state where Democrats had mostly reigned for more than a century, has profoundly changed the working relationship of state government with its two remaining Democratic strongholds.

In the decade since, Tennessee’s reform-minded legislature has singled out Memphis and Nashville for multiple controversial education initiatives, even if their locally elected officials oppose them. GOP leaders point to the high concentrations of low-performing schools that have languished in both cities as justification to intervene.

Beginning in 2012, the state took over dozens of schools in Memphis and a few in Nashville through its Achievement School District. The takeovers, which handed control to charter operators that for the most part have also struggled to improve the schools, angered people in neighborhoods where schools were a source of pride.

The legislature also approved measures aimed at luring private charter organizations to use public money to open and operate schools that are supposed to use innovative teaching methods. Memphis begrudgingly became home to most of the charter schools, while Nashville’s school board pushed back the hardest.

More recently, the legislature passed a school voucher law that would give taxpayer money to eligible families who leave public schools to pursue a private education. The 2019 law, which was championed by the governor, only applied to Memphis and Nashville, opening the door to a successful legal challenge. The state has appealed the ruling.

In separate litigation, Memphis and Nashville school boards are challenging the adequacy of state education funding, especially for urban schools. Their 5-year-old lawsuit, which is set for trial in October, aligns with Democrats’ calls to invest more money in education in a state that still ranks near the bottom in per-pupil spending.

The lawsuits have infuriated state Republican leaders, while providing recourse for local officials who believe Capitol Hill isn’t giving them a fair shake.

“Since 2010, the legislature has kind of quit listening to the people on the ground in its biggest urban areas, especially in Memphis,” said Marcus Pohlmann, professor emeritus of political science at Rhodes College. “They’ve imposed policies that are premised on the idea that school choice is pretty much the answer to everything.”

Many urban educators long have argued for an approach that is more comprehensive — and expensive. Their want list includes expanding early childhood education and wraparound programs that combat poverty and improve health care.

“It’s just like playing whack-a-mole if you’re not trying to solve the systemic problem,” said Miska Clay Bibbs, school board chairman for Shelby County Schools.

‘Race cannot be ignored’

Tennessee’s school reopening debate has centered on the state’s two most diverse school systems, which also are led by Black superintendents.

“The undercurrents of race cannot be ignored,” said Sen. Raumesh Akbari, a Memphis Democrat.

“The official line is that this is not about race,” said Akbari, who is Black. “But it’s difficult for Memphians to think otherwise when folks from other places in our state are trying to decide what’s best for Memphis and Shelby County, and it’s in conflict with the decisions of local school leaders who know their community best.”

Trust in state government, including its predominantly white legislature, is particularly low in her hometown, she said. About 65% of the population is Black.

Memphians are still smarting over legislative decisions that prompted the school board to give up its charter for Memphis City Schools, which served students who were mostly of color and from low-income families. That move led the city district to merge in 2013 with the suburban Shelby County district, which served more affluent students who were mostly white.

A year later, six suburban towns seceded and created their own school systems after Republican legislators passed a new law to allow it. Their exodus is considered one of the nation’s most egregious examples of public education splintering into a system of haves and have-nots over race and class.

“That was a big thing,” recalls Councilman Jones, who served on the city school board before schools were desegregated, then quickly resegregated. “It led to a lot of mistrust, and that has never dissipated.”

Dianechia Fields’ mistrust only grew when she began traveling to the Capitol in 2016 to lobby for education policy changes with the parent advocacy group Memphis Lift. Fields, who is Black and has two sons in Memphis schools, was surprised by how little rural white legislators knew about the state’s largest school district and the experiences of Black parents and students. One lawmaker remarked that he didn’t know Memphis parents cared about their children’s education.

“That was eye-opening,” she said. “They didn’t know. They just knew what they saw on paper. But none of them had visited schools to see what was actually happening.”

Multiple surveys conducted by Shelby County Schools show parents and educators have serious concerns about whether schools can keep students and teachers safe from the virus. Most say they don’t want to return to classrooms due to their city’s large number of COVID-19 cases. Many Memphis students live in crowded and multigenerational homes with older family members who are more at risk of dying if they get sick.

“The health concerns are real,” said Pohlmann, who has authored several books on education and race in Memphis. “People are dying, and the feeling is that, if you have to err, maybe you err on setting back kids’ learning a little bit in order to protect lives. Kids can recover, but dead people don’t come back.”

Who gets to decide?

Senate Majority Leader Jack Johnson said he believes in local education control, but not when it runs contrary to state policies aimed at “the best interest of kids.”

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recently said there’s little evidence of coronavirus transmission in schools if precautions are followed. By contrast, staying remote has put a strain on students’ mental health and compromised access to food for children from impoverished families. Other data shows that Black and Hispanic students, as well as those in schools that serve low-income students, are falling further behind in reading and math.

“The state sets the parameters in which the [school systems] operate and provides about two-thirds of the funding,” said Johnson, who represents an affluent district south of Nashville and co-sponsored the bill to tie funding to reopening. “When they are not adhering to the letter or spirit of those parameters, we have every right to intervene — and we will.”

Johnson has little patience at this point for school systems that don’t offer an in-person learning option. “These are massive school systems. They have enormous facilities. They’ve had ample warning and plenty of time,” he said.

But that kind of top-down talk feels more like a “master-slave narrative” in which “I know what’s best for you,” says Natalie McKinney, a former policy director for Shelby County Schools.

“We cannot purport to say we’re changing something for the better for someone and we don’t include them in that process,” she said.

Others worry that choosing a combative tone ultimately will be counterproductive.

“Power dynamics go both ways,” said Joshua Glazer, an education policy professor at George Washington University, who has studied education and race in Memphis. “Local districts depend on the state for funding. And the governor and state education agency really need school districts to carry through and implement their plans. There’s a web of interpendence here where all these different players really need to work together.”

Unfortunately, Glazer said, the divide over how to best reopen schools follows years of other disagreements that have created a debilitating level of mistrust between the state and districts in Memphis and Nashville. Without a history of healthy institutional relationships to fall back on, he said, “things can very easily spiral downward, which it seems to be doing.”

“COVID didn’t invent these problems; it just put them in the limelight,” Glazer continued. “And there’s no vaccine that will cure when cities and the state can’t work together.”