Recently, people have been pushing for the wrong changes to Tennessee state curriculum. This past May, Tennessee passed a law that restricts the way students can be taught about race, including banning concepts related to critical race theory and any teaching that the United States or meritocracy is inherently racist or oppressive. This controversy has distracted from what is genuinely problematic in existing curricula: the whitewashing of history and the erasure of the experiences of Tennesseans of color.

This issue was made even more evident recently, when the legislature’s joint Education Committee failed to make time to discuss Chattanooga Democratic Rep. Yusef Hakeem’s bill to expand Black History curriculum for middle school students. In response to this move, Hakeem questioned Tennessee’s commitment to teach an inclusive history curriculum. He’s right; Tennessee’s current history curriculum places emphasis on the white experience — the most blatant example of which can be seen in the state standards for the Tennessee History course taught in public high schools across the state.

As I read through the social studies standards for a curriculum writing project I was working on, the language stopped me in my tracks. Nestled between the unit on the War of 1812 and that on the Civil War is a title that stands out: “Tennessee’s Golden Age (1800-1860).”

The subtitle clarifies that during the unit, “Students will examine the changes to Tennessee’s economy, contributions of important Tennesseans, and the growth of slavery in Tennessee prior to the Civil War.” The content standards, which list out the major events of the era, include the Indian Removal Act, the Trail of Tears, the expansion of slavery, and the Tennessee Constitution of 1834, which prohibited free Black people from voting.

For whom was this era golden? This immediately struck me as a clear-cut glorification of the pre-Civil War South.

Finding no mention in the course content for why it was called a “golden age,” I dug deeper. The state history course is based heavily on Tennessee’s Blue Book, a document which “serves as a manual of useful information on our state and government, both past and present,” according to the website for the Tennessee Secretary of State. The Blue Book effectively serves as the codified history of Tennessee, the story that we have decided is ours.

In the Tennessee Blue Book, there is no chapter that is titled “Tennessee’s Golden Age.” The equivalent time period is referred to as “The Age of Jackson” and the content elaborates on the standards from the unit. But the book states that the “period from 1820-1850 was a golden age for Tennessee politics — a time when the state’s political leaders wielded considerable influence in the affairs of the nation” and goes on to say that the election of Andrew Jackson to the presidency “ushered in the triumph of western democracy.” According to the book, with the election of Jackson “the torch passed to the heroes of the common man.”

It would serve us well to reexamine the way we teach Tennessee’s history to the next generation and make it more inclusive.

This description does little to foreshadow the horrors that were to come from this era, many of which were the direct result of policies enacted by Jackson and the other Tennessee leaders whose power supposedly made this age “golden.” We cannot disconnect the power that Tennesseans held with what it was used for. During this time, approximately 16,000 Cherokee people were forcibly removed from their homelands and over 4,000 were killed in the process. By 1860, there were over 275,000 Black people enslaved in the state of Tennessee.

The unit that follows “Tennessee’s Golden Age” in the Tennessee History course is titled “A Time of Troubles.” It discusses the role of Tennessee in the Civil War. Calling the Civil War a time of troubles hardly does justice to the era. Moreover, the juxtaposition of these two units suggests a clear narrative: that the pre-Civil War era in Tennessee was good and that the Civil War, a war which ultimately led to the end of slavery in the United States, was the onset of trouble for the state.

This language appears in the latest set of state social studies standards, adopted in 2017 by the State Board of Education, a board which currently has only one Black member, Darrell Cobbins of District 9. Small changes, such as retitling the “Tennessee’s Golden Age” unit to “Tennessee During the Pre-Civil War Era” and “A Time of Troubles” to “The Civil War,” or something similar, would right glaring wrongs in the standards for this course. And it would serve us well to go beyond that, to take this opportunity to reexamine the way we teach Tennessee’s history to the next generation and make it more inclusive.

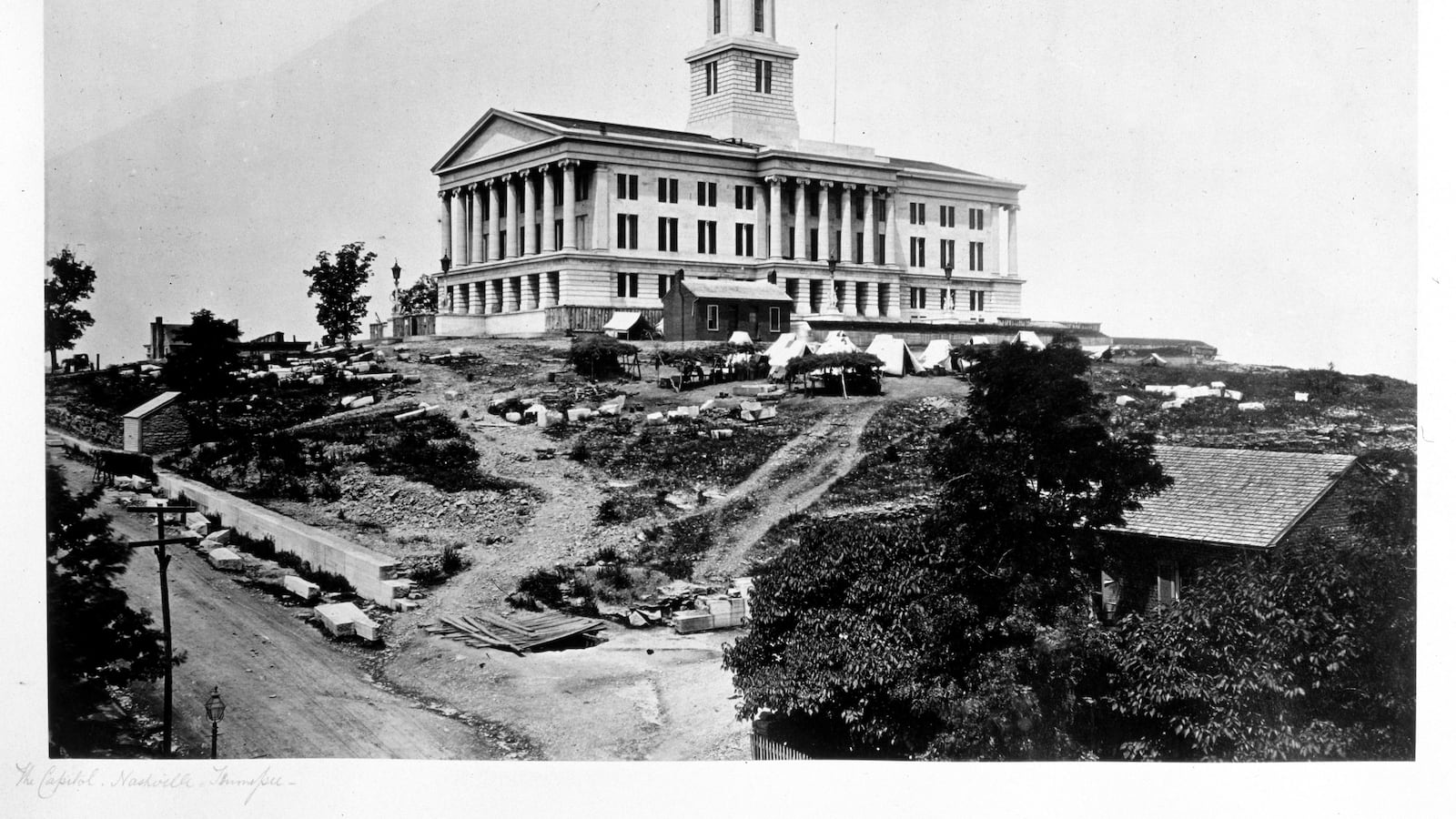

Suggesting these types of changes will no doubt lead to protests. Tennessee is no stranger to the “But it’s history!” argument in response to the removal of monuments to racism in the state, both figurative and literal. It took until the summer of 2021 for a bust of Nathan Bedford Forrest, a human trafficker and grand wizard in the Ku Klux Klan, to be removed from the State Capitol. In response, Lt. Gov. Randy McNally, who voted against the removal, complained that “The woke mob means ultimately to uproot and discard not just Southern symbols, but American heroes and history as well” and that if we judge past figures using modern standards “we would have no Tennessee heroes, only villains.”

McNally is correct in that we will have to look outside of traditional historical narratives to find role models for modern-day students. But if we want to chart a path forward to an era in Tennessee that is truly “golden,” an era in which all of the state’s residents are treated with respect and have their basic needs met, we can start with owning up to the past. And if what this course wants to do is make students proud to be from Tennessee, there is no dearth of incredible leaders that we could highlight, people who truly made the state better for all Tennesseans: John Lewis, Elihu Embree, J.W. Loguen, Avon Williams, Ida B. Wells, Edward Shaw, John Rankin, Septima Clark, and Maxine Smith, to name just a few.

I’m not suggesting that we change established facts or “discard” history as we reexamine the narrative we are passing on to Tennessee youth. There is nothing wrong with acknowledging that the period from 1800-1860 was historically referred to as “Tennessee’s Golden Age.” Doing so offers an important window into the sentiments of white male powerholding Tennesseans at the time and acknowledges the undeniable fact that Tennessee is a state built off the wealth of slavery. We should absolutely talk about the economic, social, and political realities of that time, including the actions of Jackson and the other leaders who gained power during the era.

However, we should do so in a way that doesn’t erase the experience of many of the state’s residents. After all, wielding power alone does not make an era golden, not when the power was built on the backs of enslaved people and used to continue to oppress vast portions of the population.

As Dr. Toni Morrison said, “Oppressive language does more than represent violence; it is violence; does more than represent the limits of knowledge; it limits knowledge.” Teaching a history that fundamentally devalues the experiences of entire groups of people while reinforcing outdated narratives about the South is not apolitical, is not benign.

As an educator who has taught and written environmental and place-based curriculum for students ages 3-18, I am accustomed to thinking about how our education system has the power to shape students’ attitudes and understanding of the world. When I imagine the pre-school students I am currently working with continuing their education, I hope that the classes they take give them the tools to think critically about the past and future of the state they call home.

Revisiting the Tennessee History curriculum is a real opportunity to examine the narratives we are passing on to young people in Tennessee, starting with changing the language around “Tennessee’s Golden Age” and going on to expand the range of voices whose experiences are recounted in our schools, as Hakeem hoped to do with the Black History curriculum.

It seems we’ll have to wait for the course Hakeem envisioned for middle schoolers. In the meantime, we can strive to include more perspectives in existing courses. The social studies academic standards review process begins again in fall 2022. Let your voice be heard.

Morgan Florsheim is an educator and writer based in Nashville.