Several Memphis student advocacy groups want sheriff’s deputies removed from schools and the $2 million that covers their salaries and benefits diverted to hiring counselors and funding more mental health services.

Anahis Luna, a member of the Shelby County Youth Council and student advocacy organization BRIDGES, asked the Shelby County Commission to reallocate the money from the Sheriff’s Office to Shelby County Schools.

“They’re everywhere,” she told county commissioners during Monday’s meeting via videoconference. “They’re always there to put you in place if you ever mess up.”

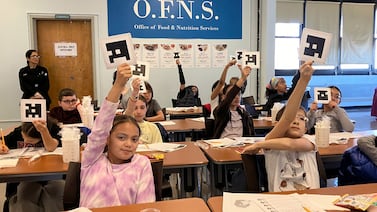

Luna spoke on behalf of a coalition of BRIDGES students working to reduce referrals to juvenile court, protect LGBTQ students, and end sexual harassment among students. Education advocacy organization Stand for Children is also working with the students on the request.

The students join a growing movement of renewed calls to remove law enforcement officers from schools after a white police officer killed a Black man, George Floyd, in Minneapolis.

Districts in Minneapolis and Portland have terminated their contracts with police departments, while pressure is mounting to do the same in Chicago, New York City, and Detroit. Denver school officials plan to phase out police by next summer.

Security staff in schools are generally known as school resource officers and can include police officers, sheriff’s deputies, contracted private security, or district-employed security. Shelby County Schools uses few deputies and mostly relies on district-employed school resource officers. Those district officers do not carry guns but have pepper spray, the district said.

Last school year, 18 school resource officers were deputies, all paid for by the Sheriff’s Office. The district’s agreement for the 2019-2020 school year allows for as many as 36 deputies. Eventually, the coalition wants all school resource officers — deputies and district-employed — to be removed from schools.

The district spends $5.1 million on about 130 in-house school resource officers. That amount is part of $14 million the district spends on safety and security, including violence prevention programs, cameras, card access systems, intrusion alarms, and fingerprinting, according to budget documents.

District officials in a statement defended using school resource officers and its broader safety and security team, attributing a decline in gang violence, serious incidents, and referrals to juvenile court to their efforts. The safety and security team works on, among other initiatives, violence prevention programs.

The district said gang activity has decreased 25% in schools in recent years and the number of serious incidents have declined for the sixth consecutive year. A prevention program offers school-based counseling services to help cope with trauma or anxiety along with conflict resolution. Since the 2014-15 school year, the district has seen a 59% decrease in incidents of disruptive or violent behavior, the statement said.

The students recognized the need for systems to keep students and staff safe. Throughout the year, the students plan to gather input from teachers and principals on how to increase safety in the absence of deputies in schools.

Few studies have been done on whether school resource officers deter school shootings or reduce overall violence. But a 2017 national study found that more children are arrested when police are added to their school and in Texas, the presence of officers led to higher suspension rates for low-level offenses.

Luna, who will be a senior in the fall, also said school resource officers can perpetuate violence. When she attended Overton High School, she said she saw a school resource officer break up a fight by dragging a student to the principal’s office. To her, whether or not the officer is armed is unimportant because his or her presence sends a message: “He’s here to intimidate me. He’s here to keep me in line.”

Instead, she wants to see more restorative justice practices where students talk out their conflict as alternatives to out-of-school suspensions.

“Why were they fighting? Get to the root of the problem and really try to instill values that kids should be able to have,” she said.

Kaleb Sy, a sophomore at East High School and a member of the youth council, agreed that he would rather see restorative justice practices in schools, but he stopped short of calling to remove all school resource officers. He would rather remove armed sheriff’s deputies, who have power to arrest students.

“I don’t want the students who I serve to feel like the Little Rock 9 being escorted to the steps of historic East High,” Sy told Chalkbeat. But “if we repeal all law enforcement in schools, how will schools be protected? We’ve seen it with Sandy Hook and Columbine,” he said of mass shootings in schools.

Sy said he would also like for students to oversee implementation of more mental health resources and emotional support for students.

Shelby County Schools leaders have recently considered changes to how law enforcement officers interact with students at school. In December, the board declined a request from Superintendent Joris Ray to lobby state legislators for the ability to create his own police department. Ray said he believed he could control officers’ behavior more effectively if they reported directly to the district. But some board members said mistreatment was just as likely with a district-run police force.

The call to remove law enforcement from schools in Memphis and elsewhere stands in contrast with pleas from other Tennessee districts for more money to hire school resource officers in the aftermath of the 2018 school shooting in Florida where a student killed 17 people. Shelby County Schools used state grant money to purchase security cameras and 30 school resource officers after the Florida shootings.

At Monday’s meeting, commission Chairman Mark Billingsley thanked Luna for her comments and referred her to two commissioners who oversee education and law enforcement to discuss.

Zahra Chowdhury, a junior at the private Pleasant View School in Memphis has been working with BRIDGES on student discipline issues since she was a freshman. She said the students’ request would go a long way in preventing youth arrests and promoting student emotional health.

“It’s not completely preposterous or outlandish,” she said. “People have done it elsewhere, we can do it here now.”