Tennessee’s two largest districts are deciding whether to open new charter schools while also navigating a pandemic-induced upheaval to public education that could cut spending on existing schools.

School boards in Memphis and Nashville will vote Tuesday on applications seeking to open nine charter schools in the fall of 2021. Elsewhere, Hamilton County’s board has already approved another charter for Chattanooga, while Monroe County voted down a proposal for its rural system south of Knoxville.

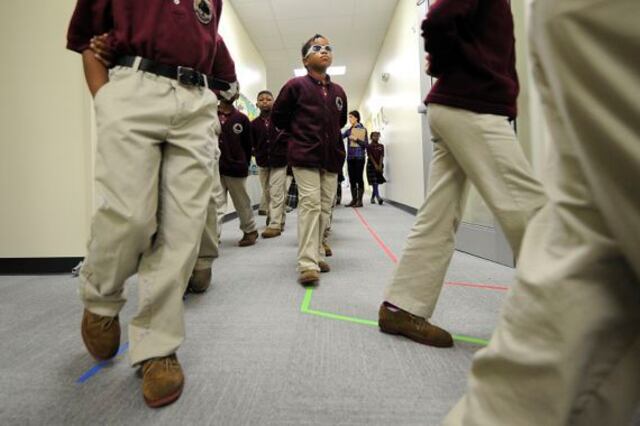

The votes are part of an annual application process that began when a 2002 state law opened the door to public charter schools. Tennessee now has 118 of the publicly funded, independently operated schools, the vast majority in Memphis.

But such decisions have never before been made amid a pandemic.

The coronavirus has ground most of the economy to a halt and created financial uncertainty for both traditional and charter schools. Most districts are curtailing spending, canceling school construction projects, and rethinking planned increases in teacher pay. Earlier this week in Memphis, charter network KIPP announced plans to close two of its schools, partly because of its struggle to secure long term-funding during the pandemic.

“The whole situation has really affected budgets,” said state Rep. Antonio Parkinson of Memphis. “Right now, it’s as ludicrous to be considering opening new charter schools as it is to launch a school voucher program.”

Elsewhere in the nation, the public health emergency has prompted a number of charter pivots and controversies. In New York City, KIPP postponed its opening of an “intentionally integrated” charter school in Harlem due to concerns about student health. In Los Angeles, the teacher’s union called for a moratorium on new charters and a halt to new campus-sharing arrangements with charters because of the crisis.

Tennessee’s charter debate has centered on whether charters drain money from already underfunded districts by shifting per-pupil funding. The new budget crunches have amplified that concern.

Earlier this month, Mayor John Cooper asked Metropolitan Nashville Public Schools to look for ways to cut up to $100 million from its current budget as the city’s revenue collections cratered.

“We have a limited pool of funds,” said Nashville board member Amy Frogge, a charter school critic who plans to vote to deny the district’s five applications. “We can choose to pay our teachers or open more charter seats.”

Shelby County Mayor Lee Harris hopes to spare Memphis-area districts from budget cuts by increasing car registration fees. However, his proposal is expected to be a tough sell in an economic slowdown.

“This is just the wrong time to be looking at charter applications,” said Parkinson, a Democrat who says local boards should be able to deny charters this year without facing repercussions from the state.

Charter advocates believe this is actually the right time to look for ways to innovate in education. Innovation is the original idea behind charter schools, which have more flexibility to set curriculum, school hours, and rules than traditional public schools.

“We can’t just drop a hammer and say no more charters because we’re in a crisis,” said Maya Bugg, executive director of the Tennessee Charter School Center. “We have to be smart about how to continue creating high-quality options in the midst of crisis.”

Bugg added: “This isn’t a traditional versus charter thing. This is an all-hands-on-deck thing. We need to be innovative and collaborative in our thinking.”

It’s unlikely that any of the remaining applications will gain initial approval this year.

In Memphis, the district has recommended its board deny all four applications based both on state and local standards that include academics, operations, and finance.

Nashville’s new director, Adrienne Battle, opted against making a recommendation on that district’s five applications, including three from KIPP. But a packet sent in advance to board members says none of the applicants met all of the standards.

If denied, applicants can submit an amended application that the board must vote on by Aug. 1. If voted down again, they can appeal to the State Board of Education.

The timeline for the votes was moved up this year under a 2019 law that also created a new state charter school commission to take over appeals beginning in 2021. The intent, said House Education Chairman Mark White, is to provide more time for a thorough review of applications.

“We’ve all been thrown into this state of wondering what’s next because of the pandemic, but it shouldn’t diminish the fact that we need deadlines so that all parties can move forward in one way or another,” said White, a Memphis Republican who co-sponsored the law.

“Whether you like charters or not, this is the law in Tennessee,” he said, “and charter schools are part of our public education system.”

You can see the new application timeline here.