Tennessee has had nearly a decade to figure out an exit plan for schools in its embattled turnaround district. It has six weeks left, and a final draft appears to be imminent.

Last summer, the legislature gave the state education department until Jan. 1 to come up with its blueprint for 27 schools and about 8,000 students to leave the Achievement School District and return to their local systems in Memphis and Nashville.

Because the transition involves everything from people and property to finances and governance, state officials have found it almost as hard — and complicated — to return schools as it was to take them away.

The department will present some of its proposals this week in three community meetings. The gatherings, held online due to the pandemic, will also collect feedback from families and neighborhoods that will be most affected when their schools depart from the state-run district.

The handoff will begin with a handful of schools in the 2024-25 academic year, but lawmakers could decide to speed up that timeline.

Either way, the changes will mark a new chapter in the so-called ASD, the state’s lever for trying to turn around Tennessee’s lowest-performing schools.

After nine years of generally disappointing results in taking over struggling neighborhood schools and mostly handing them off to charter networks, Tennessee officials acknowledged this year that their most ambitious school turnaround model failed miserably. But instead of chucking the whole thing, Gov. Bill Lee and his education commissioner, Penny Schwinn, plan to reboot the program and launch “ASD 2.0.”

“First and foremost, the state is committed to the ASD as the highest form of intervention for our schools that have been consistently low-performing,” Schwinn said earlier this year. “That has been a strong position of our state, and we are not wavering there.”

Tennessee has yet to unveil its revamped turnaround structure. First, the state must decide what to do with schools languishing in its current ASD model. They’ll need a place to land as 10-year contracts with charter management organizations expire, beginning with the first schools that entered the district in 2011.

“The ASD was not intended to be any school’s forever home, and we still believe it should not be,” said Eve Carney, who is leading the transition work on behalf of the department. “As such, there is a need for a thoughtful transition plan for schools that are ready to exit.”

But lots of unanswered questions remain. Will the schools stay with charter management organizations? Will their local districts want schools back if they’ve not improved? What if a charter group wants to continue managing a school but not move under the authority of the home district?

Since August, Carney has convened an advisory group of 18 state and community education leaders to work through the issues. They include school board members from Memphis and Nashville.

Recently, she presented some of their ideas to the state’s newly formed Public Charter School Commission, which will adjudicate any disagreements over exiting schools.

“This is really not a one-size-fits-all type of plan, and should not be,” said Carney, the department’s chief districts and schools officer. “We acknowledge and want to respect the fact that every school is unique.”

Carney pledged that each school’s exit plan will be developed collaboratively by leaders of the school, the originating district, and the ASD — not exclusively from state offices in Nashville.

“It really is about not forgetting about the families and communities that these schools belong to,” she said. “I’d like to believe we’ve learned lots of lessons in this past decade and that we are going to move forward differently because of those.”

One of the biggest lessons: Listen to the people who know the schools and their communities the best.

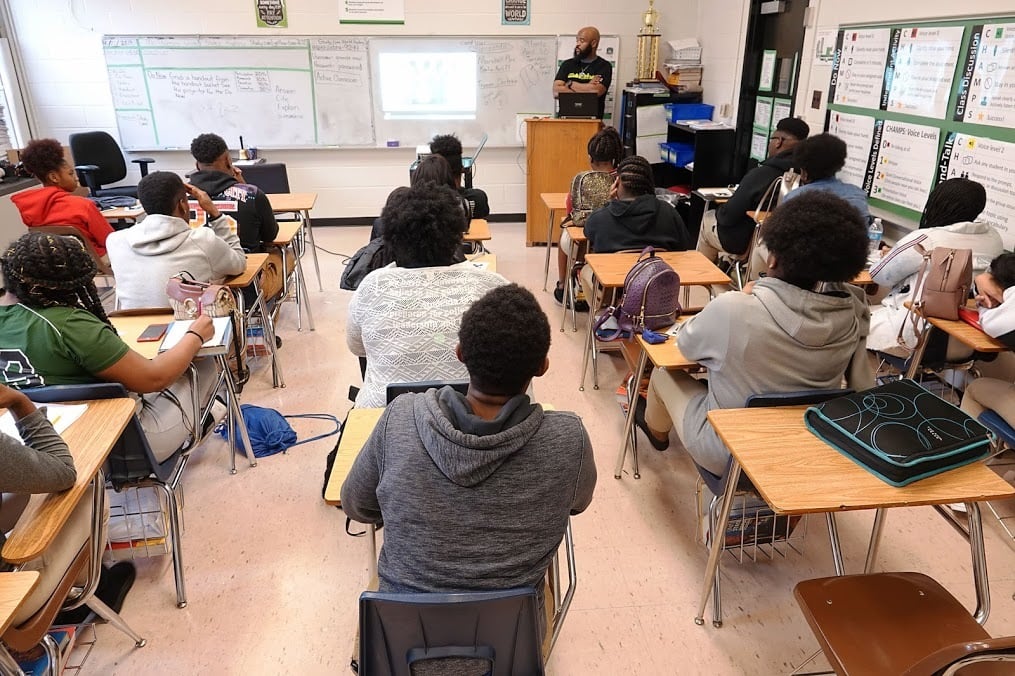

The ASD launched in 2011 in an era of school reform. Mostly beginning in Memphis, the state took control of schools that were chronically low performing but also served as important community hubs. While the interventions inspired an urgency to improve other local schools, many Memphians haven’t forgiven the state for its heavy-handed takeover tactics ordered from Nashville.

Tennessee’s education department is trying now to do a better job of engaging with communities on what comes next. State officials hope for a good turnout at this week’s meetings, although the pandemic presents new challenges to already challenging engagement work.

“Families sometimes feel like these kinds of meetings are just to check the box – that their feedback won’t really be taken into account,” said Bobby White, CEO of Frayser Community Schools, a Memphis-based charter network that includes three ASD schools and a total of 1,200 students.

“I’m hopeful this isn’t just lip service. Our parents are tired of feeling like people talk at them,” he said.

Ultimately, the exit plan should look at each individual school for ways to continue successes and improve shortcomings, said Bob Nardo, founder and executive director of Libertas School of Memphis.

Also part of the ASD, Libertas is Tennessee’s only Montessori charter school and has shown growth in both student performance and enrollment.

“I think most of our families don’t know much about big abstractions like the ASD or Shelby County Schools,” Nardo said. “They’re mostly just concerned about their child’s school. The last thing they need now is to destabilize any trajectory of success.”