One of two registered nurses covering nine schools in a rural Tennessee district, Jennifer Patterson tends to the healthcare of about 2,500 students whose needs have only increased during the coronavirus pandemic.

Her days are full — from answering questions about COVID and providing routine care to keeping up with immunization records and sometimes helping with medically fragile special education students.

Now the prospect of giving a new rapid coronavirus test to symptomatic students and staff has the veteran nurse thinking about how she could manage that additional responsibility.

“I think it would be very tough,” said Patterson, who works for McMinn County Schools, a sprawling district south of Knoxville. “We’re a rural county and our schools are far apart. I think my phone would be going off all the time. And if I’m dealing with seizures or a tube feeding, I couldn’t drop that to go do a COVID test.”

Gov. Bill Lee wants to prioritize testing for the coronavirus in schools when the first shipment of 133,000 rapid tests arrives this month from the federal government. By the end of the year, the state is due to get 2 million of the kits, which aren’t as accurate as laboratory tests but deliver results in minutes, not days.

His administration is getting pushback, however, from district leaders concerned about the logistics of turning schools into COVID testing sites.

“Our two nurses can’t be everywhere. Their plates are already very full,” said Lee Parkinson, director of schools in McMinn County, where Patterson works. “We also have nurse aides who work specifically with our special education students handling needs like medication and catheters. But their first priority has got to be those students.”

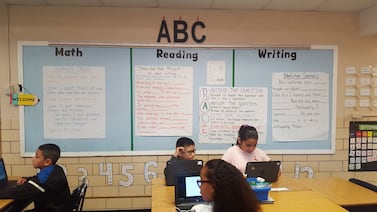

The coronavirus has highlighted the importance nationally of school nurses, considered front-line workers in public healthcare. In some cases, they provide the only medical care received by students from low-income families.

But in Tennessee, only 60% of public schools had a full-time nurse in 2018-19, according to a report released in February by the state comptroller’s office. That falls significantly short of recommendations by the American Academy of Pediatrics and the National Association of School Nurses, which both say a full-time nurse should staff every school.

Most of the school nursing positions in Tennessee are funded locally because of the way the state’s education funding formula works. The state pays for one full-time nurse for each of its 147 school districts, plus additional funding to hire one school nurse for every 3,000 students.

Lawmakers have introduced several bills to improve that ratio, but none have been prioritized. A $42 million proposal, sponsored by Rep. David Hawk of Greeneville, stalled in committee last spring.

“It’s a broad need,” Hawk said after failing to get traction on his bill for a second straight year. “For whatever reason, our students have more medical needs than ever before. If the state stepped in with more money, it would free up a lot of local dollars for educational needs.”

For now, schools are using the resources they have to manage the public health emergency. Nationally, as school buildings have reopened, the number of children infected with COVID has increased dramatically — more than 14% in the last two weeks alone, according to new research by the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

Testing is key to taming the virus, but the prospect of giving new rapid tests in schools isn’t exciting district leaders across Tennessee, even those with a nurse on every campus.

“Our nurses are already at capacity for their regular duties on a daily basis,” said Linda Cash, superintendent of Bradley County Schools, near Chattanooga. “We would prefer the rapid tests go to local medical providers.”

Terry Weeks, superintendent of Dickson County Schools, near Nashville, said he’s not inclined to add another chore for his district’s nurses either — but not just because their plates are already full.

“I just don’t see a benefit at this point,” said Weeks on behalf of his 8,000 students and 16 schools. “If you had symptoms and we gave you the rapid test, we would have to send you home either way.”

Similar to a home pregnancy test, the new antigen test, which was developed by Abbott Laboratories and purchased by the federal government, is fairly simple to administer. It requires swabbing the lower nose and placing the swab on a small card to watch for a chemical reaction. Within 15 minutes, it detects whether the virus is present.

But state health officials have told superintendents that the test still should be given by a licensed healthcare professional.

If the governor sticks with his intention, that could mean one more responsibility for school nurses, many of whom are already helping their local health departments with contact tracing for students and staff who test positive.

“This work is important. However, it has added to the normal and customary role of the school nurse,” said Vicki Johnston, a nurse supervisor in Kingsport and president of the Tennessee Association of School Nurses.

That points to a bigger issue, Johnston said.

“Students in Tennessee deserve to have a full-time nurse on campus in order to meet daily medical needs, as well as increased medical needs related to COVID-19,” she said.