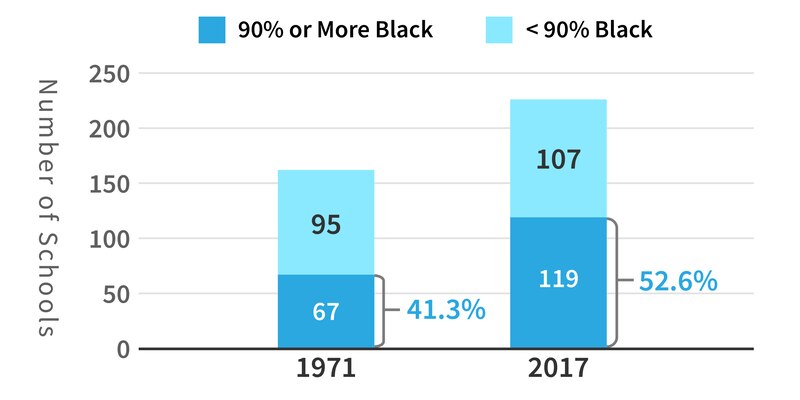

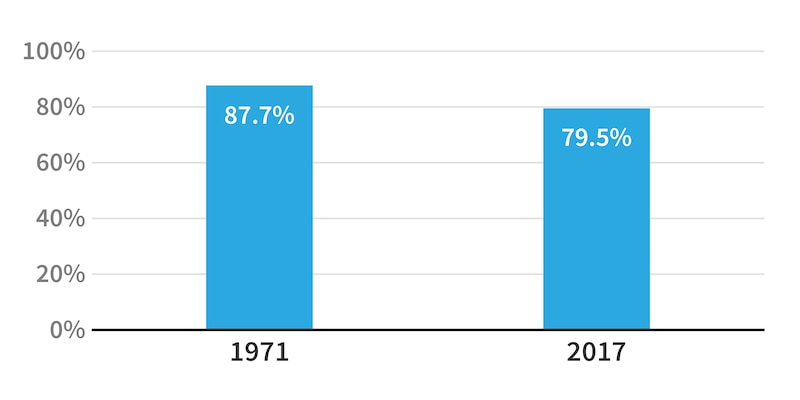

Schools in Memphis have become increasingly segregated over the last 50 years, according to a Chalkbeat analysis.

A little more than half of Memphis schools are highly segregated, in which 90 percent or more of students are black. That’s up from about 40 percent in 1971 when a Memphis judge used those statistics to call for a plan to end school segregation.

Add in Hispanic children, whose share of the student population has dramatically increased since then, and more than 80 percent of schools are highly segregated.

Share of highly segregated Memphis schools

And without a re-entry of white families into the city’s school system and massive policy changes, the segregation will only worsen, say academics who have traced Memphis African-American and education history.

The numbers in Chalkbeat’s analysis, like the 1971 ruling by Judge Robert McRae Jr. that ushered in an unpopular busing plan that failed to achieve integration as white families fled the city, do not include private or suburban schools.

According to Marcus Pohlmann, author of “Opportunity Lost,” which chronicles Memphis education history, the two largest events that created the “obvious resegregation” of schools in Tennessee’s largest district were: white families fleeing public schools in masse after desegregation orders went into effect in the 1970s; and the creation of six suburban districts in 2014, which dismantled the historic merger of the mostly black and poor city school system with a largely white and affluent county district.

“Any hope of maybe tweaking the boundaries of this large countywide school system to reduce that to a degree, disappeared,” Pohlmann said.

Memphis is hardly alone in this trend. Federal data shows the share of schools with high percentages of poor and black or Hispanic students grew from 9 to 16 percent between 2000 and 2014. Those students often had fewer college preparatory classes and had higher rates of being held back in ninth grade. And after school districts dismantled assignment systems meant to spur integration as court orders were lifted, researchers found black and Hispanic students began dropping out at higher rates.

But unlike other cities, Memphis can’t claim a resurgence in segregated schools, says Daniel Kiel, a University of Memphis professor who has researched local school segregation.

“It’s hard to say schools resegregated when they never stopped being segregated in any meaningful way,” he told Chalkbeat.

As the nation prepares to commemorate the legacy of Martin Luther King Jr. and his fight for equality on the 50th anniversary of his assassination in Memphis, Chalkbeat’s analysis of segregation in schools show how little has changed.

“I cannot see how the Negro will be totally liberated from the crushing weight of poor education, squalid housing and economic strangulation until he is integrated, with power, into every level of American life,” he said in his last book in 1967, “Where do we go from here: Chaos or Community?”

Charles McKinney, the chair of Africana studies at Rhodes College, said the demographic comparison is “a confirmation of what we already know.”

“Some of the primary indicators of poverty and inequality are largely unmoved over the course of the last 50 years,” he said. “This should not be a surprise. Anyone who acts surprised now, just isn’t paying attention.”

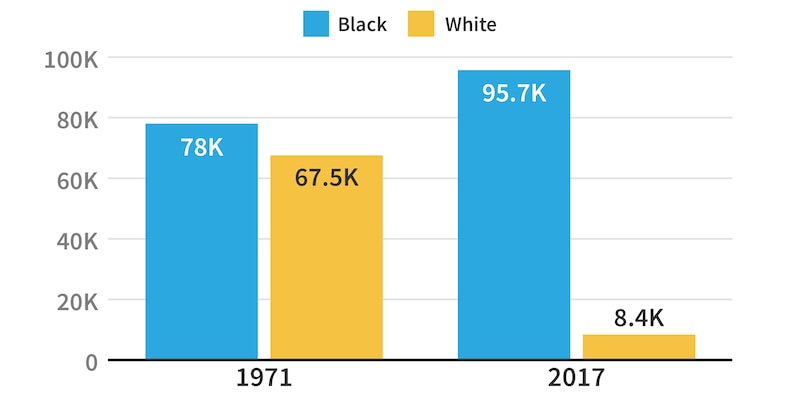

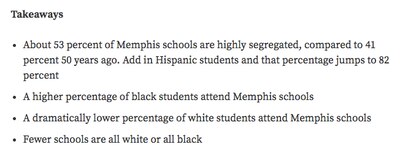

The shift in student demographics of Memphis schools over the last half-century —from 46 to 7 percent white — is one of the most revealing changes. Black students increased from 54 to 79 percent of Memphis schools.

Memphis student racial makeup

Despite the stark differences, there are fewer schools now that are all black and none that are all white. In 1971, there were 29 schools that were all black and 18 that were all white. Now, just three Memphis schools are all black and none are all white, according to state data. Six are all black and Hispanic students.

About 7,700 more black students attend highly segregated schools now, though as a percentage of black students, that is slightly lower than in 1971. Add in Hispanic students and that number jumps to 16,112 more students of color in highly segregated schools.

Black students attending highly segregated schools

After several iterations of a desegregation plan in Memphis that included busing students to schools to mix up their racial demographics, thousands of white students fled the city school system and numerous private schools opened to absorb them.

Memphis City Schools attempted to entice white families to stay in the district by launching “optional schools” in the 1970s where students test into more rigorous, specialized programs. Though that measure found nominal success in retaining black middle-class and some white families, McKinney said the concept defeats the purpose of true integration. He cited programs like Maxine Smith STEAM Academy, which became an all-optional school in 2014 and East High School, which by phasing in its optional program displaces neighborhood children to other schools.

“We’ve created a formula that literally states that school quality is predicated on the removal of the kids who most need access to quality education,” he said. “That’s absurd.”

To reduce segregation in Memphis schools, Kiel said it would take both an enormous amount of will from white families to integrate Memphis schools and policy changes to dismantle the fragmented educational landscape the city has today.

“Tweaks of policies that are not accompanied by an underlying belief in the rationale for those policies — that has undercut the goals of the policies in the first place,” he said. “That’s not a failure of the policies, that’s a failure of the people’s will.”

McKinney agreed with a sentiment trumpeted by journalist Nikole Hannah-Jones, who while visiting Memphis last week said the Bluff City is a “perfectly sad place” to talk about how school segregation worsens.

“If you say you are really concerned about enduring segregation in Memphis and Shelby County, you’re the primary driver of that segregation,” he said. “So, how are you going to disinvest in segregation? You have to make a course correction.”

If trends of school segregation continue, the whole city is negatively impacted, Pohlmann said.

“Whites are less likely to be concerned with poorer predominantly black schools. Citywide social relations are damaged, especially making it harder to breakdown stereotypes,” he said.

“As long as we allow this level of economic inequality in society, things like race and class segregation in the schools are just almost inevitable.”