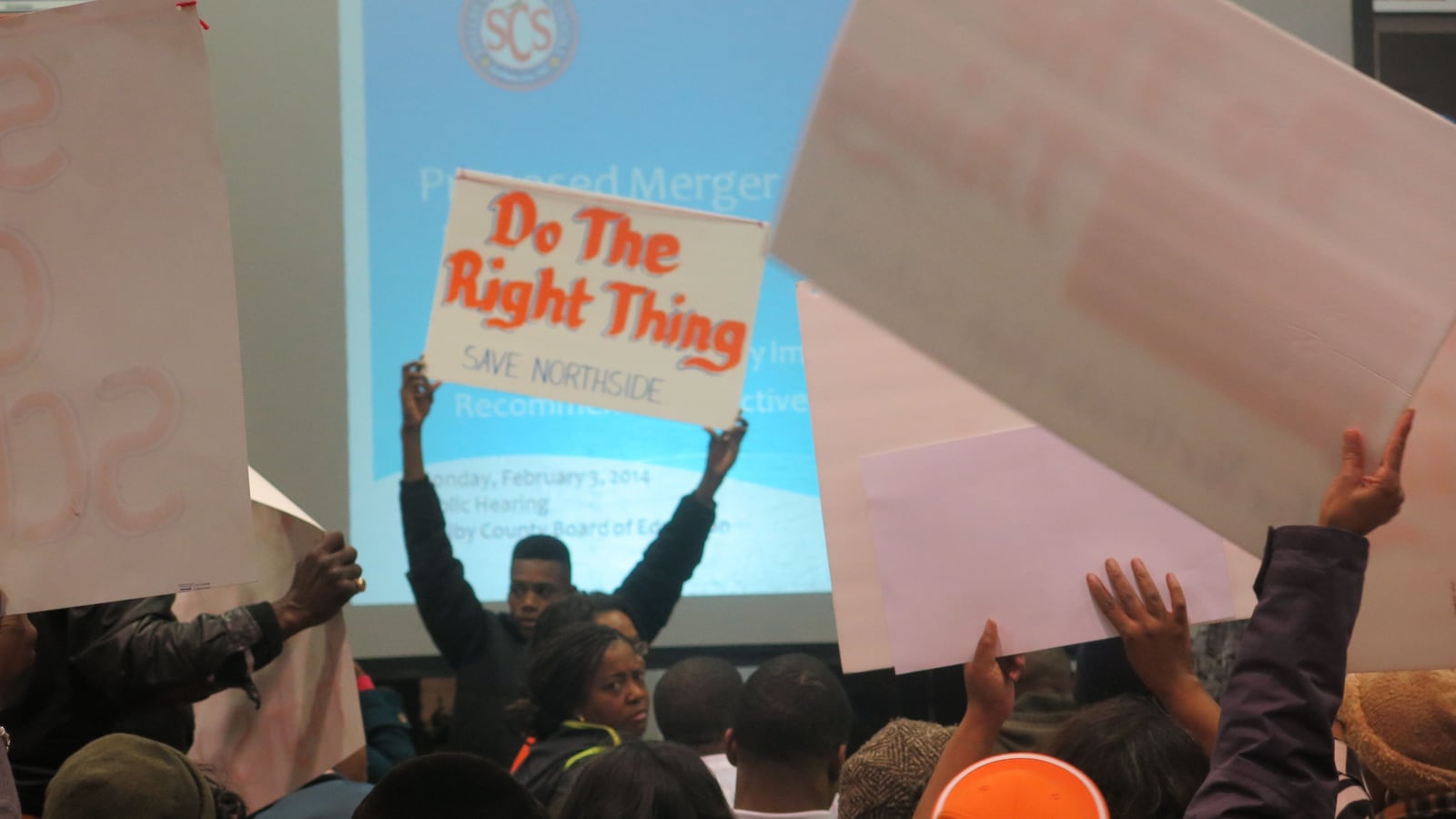

This winter, Shelby County Schools’ plan to close as many as 13 of its schools has become a flashpoint for long-running frustrations about public investment in low-income black communities and ongoing changes to local and state school policy.

Shelby County administrators say closing the buildings before the 2014-15 school year will allow them to consolidate resources and

address chronic under-enrollment, low academic performance, and deteriorating facilities. Protesters say the school closings will disrupt communities and students’ lives, and are skeptical of district claims that they will improve the quality of education.

At each of the nine schools that would sit empty next year, the district is hosting meetings aimed at allowing community members to learn about and respond to the plans. (The other four buildings will remain open as part of the state-run Achievement School District or as public charter schools.)

These meetings have quickly become about more than closings, as community members have used the public comment time to lay out concerns about the growing presence of charter schools, the erosion of popular academic and extra-curricular programs, decreasing job security for teachers and a perception that the district invests more in affluent and white communities. The closings are seen as a concrete manifestation of a deeper pattern of neglect. And the protests have quickly spilled outside the confines of the planned meetings, into vigils, rallies, and protests that are often led by clergy and echo the language and strategies of the civil rights movement.

Last Tuesday, the cafeteria at Westhaven Elementary School was a sea of brand-new t-shirts that read “I <3 Westhaven,” “We deserve a new building” and “Save our school!” The day before, dozens stood outside Northside High School on a steely cold day, holding candles and signs that read in bold letters, “Don’t Kill Our Community.” In the weeks before that, Alcy Elementary School leaders met with clergy, local politicians, and business leaders late into the evening, trying to figure out how to demonstrate that they could improve literacy rates at their school.

Board members and district officials say they are listening to community feedback and plans in order to make the best decision for students. “I have not decided what my vote will be,” board member Teresa Jones said at a meeting at Westhaven.

It is likely that many of the schools will close, as part of the district’s attempt to improve academic performance, ease budget pressures, and respond to a changing landscape that includes the planned creation of six new suburban school districts, long-term downward demographic trends, a new state-run district and a growing charter sector. Charter schools and the state-run district now educate some 12,000 of Shelby County’s more-than-150,000 students.

Urban districts around the country have closed dozens of schools in recent years, often prompted by enrollment, budgetary and academic concerns similar to those driving the plans in Memphis. Chicago’s school district closed more than 50 schools last year, and Philadelphia’s closed 24. Protesters in those cities, among others, have also described the closures as part of a pattern of neglect or disinvestment and have raised concerns about their effect on students and communities. The protests have had mixed results.

“There are schools in which community-based groups, parent groups, and locally-elected officials mobilized and put pressure on the district, which then backed down. But I don’t want to overstate how often it happens,” said Norm Fruchter, an associate at the Annenburg Institute for School Reform, which researches school closings and supports community organizing.

Jitu Brown, an organizer with the Kenwood Oakland Community Organization in Chicago, formed a coalition of groups in 24 cities, called Journey For Justice, to protest school closings. Journey For Justice has submitted complaints to the federal education department’s Office of Civil Rights alleging that closings have a disparate impact on minority students and petitioned for changes to the federal School Improvement Grant program, which funds school closings as one route to academic improvement.

“When you close a school, you’re disinvesting in that population,” Brown said. “People recognize that. That’s why I think people were willing to take chances we normally wouldn’t be willing to take.”

In Memphis, most of the activism has stayed at the individual school level. “Everyone wants to keep their school open,” said Raumesh Akbari, a state representative whose district includes Alcy Elementary School, which is slated to close.

But the past few years has seen several waves of protest involving some of the the city’s lowest-ranked schools, which are located in low-income, majority black communities. (More than four fifths of the city’s public school students are black.) The district closed four schools in 2012 and four in 2013. And community meetings at schools slated to be taken over by the state-run Achievement School District, which has taken the reins of 15 Memphis schools that were ranked in the bottom 5 percent in the state since 2012, have also drawn crowds.

A group of alumni at one of those schools, Carver High School, helped create a plan to merge with other nearby schools. Administrators approved the plan, allowing the school to stay open.

Superintendent Dorsey E. Hopson II cited Carver at a meeting this December as evidence that the district is listening to the community, and Akbari said many were inspired by the success of that plan.

“[Hopson] said, you know, what I need is a plan,” said Akbari.

At a meeting at Northside High, alumni passed out a sheet of paper contesting the district’s reasons for closing the school. Alumni are trying to garner support from all directions. “We have an outreach component, a strategy team to oversee all the communities, a social media component,” said Katrina Thompson, an alumna. “We have communicated with community leaders, state representatives, and the city council. We’ve started a petition drive, we’ve sent out postcards.”

An online petition to save Northside on Change.org has garnered more than 500 signatures.

Westhaven PTA president Bridget Bradley presented to the district a petition with 6,000 signatures and gave an emotional plea to keep the school open for the sake of its many special needs students. At the same meeting, Rev. Dwight Ray Montgomery told the school board, “If Dr. King were here today, he’d be standing where I’m standing today, unafraid.”

Reginald Porter, the district’s chief of staff, said district officials are trying to navigate a difficult situation. “Some of the decisions [people are upset about] were made 20 years ago. We’re making things right with where we are now. They have to be realistic, have to know we’re working with limited resources.”

Board members and officials have told communities that the district is aiming to improve schools. “These decisions are not made easily for us,” said Hopson at a meeting at Alcy Elemetary School. “But we have to continue to do what’s right by these kids.” Hopson urged families to channel some of their passion for the schools into helping students learn to read.

The list of 13 schools to close was released in December, and the board is slated to vote on the closings later this month.

In the meantime, “we’re scrambling,” said Kacee Franklin, an alumnus of Northside High School. “We’re going to present them a plan, but at this point we don’t have the same access to all the data that Shelby County Schools has, nor do we have the resources. Right now, they’re in closure mode. So it’s hard to say whether they’re listening or not.”